In his book Supercommunicators, Charles Duhigg shares how to unlock the secret language of connection.

In the video above and article below, I’d like to sketch out some of my favorite ideas from that book, starting with the afterword, the very last thing in the book, because for me it was a motivating factor that I think will be helpful for you to keep in mind from the beginning.

There Duhigg talks about the Harvard Study of Adult Development, which is one of the largest and longest studies ever conducted, which found that the most important variable in determining whether someone ended up happy and healthy or miserable and sick was how satisfied they were in their relationships. The people who are the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest mentally and physically at age 80. And as Duhigg writes: “In many instances, those relationships were established and kept alive via long and intimate discussions.”

This is a book about how those discussions take place, the different paths that they can go down, and how you can make them more meaningful for the purpose of supporting both the long-term relationships in your life, but also the passing conversations with strangers, and (more important than ever) those situations where there is a conflict that needs to be resolved. How do we best talk to each other in the midst of a conflict?

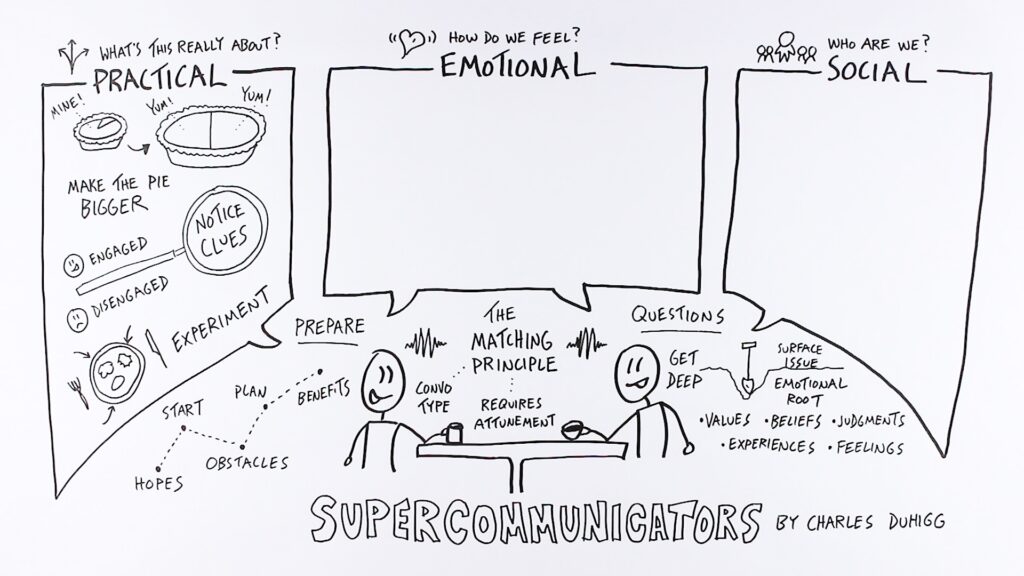

The Three Types of Conversations

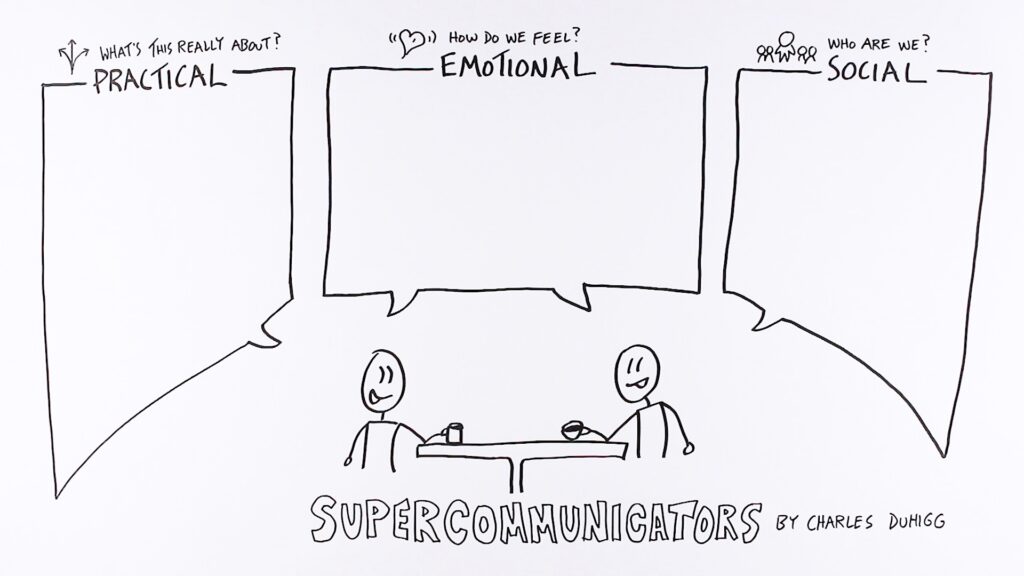

To help us answer those questions, Duhigg breaks down conversations into three categories: practical conversations, emotional conversations, and social conversations. Throughout a discussion, you will often shift from one category to another.

Practical conversations address the question: What’s this really about? What are we talking about here? What decision do we need to make? And how are we going to go about making that decision?

Emotional conversations address the question: How do we feel? And why is this particular emotion coming up in this situation?

Social conversations address the question: Who are we? What identity or identities are at play here?

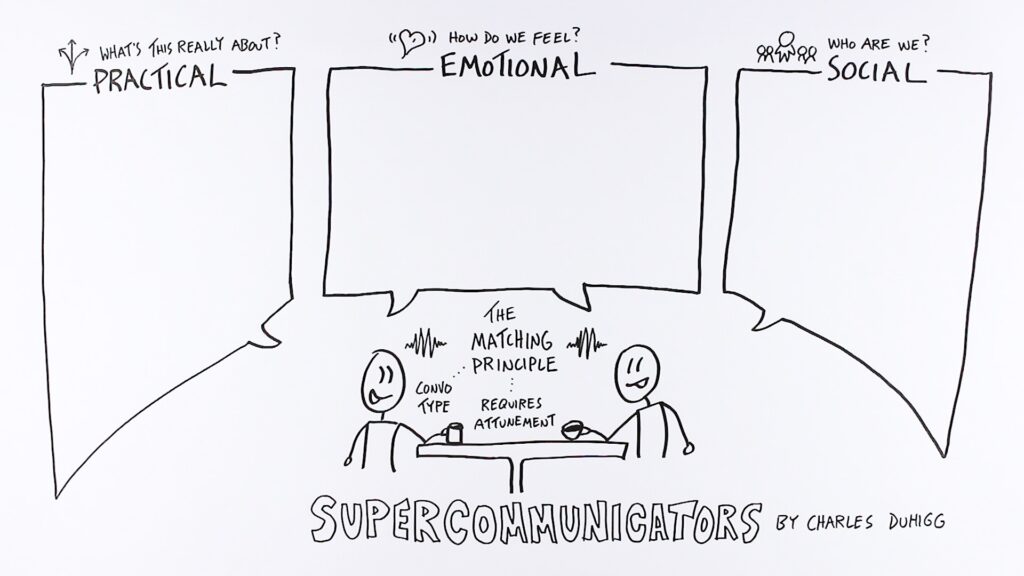

The Matching Principle

No matter where it lands in any given moment, one of the keys to a good conversation is that you’re on the same page, what Duhigg calls the matching principle. He writes: “Effective communication requires recognizing what kind of conversation is occurring and then matching each other. On a very basic level, if someone seems emotional, allow yourself to become emotional as well. If someone is intent on decision making, match that focus. If they’re preoccupied by social implications, reflect their fixation back at them.”

That type of matching requires attunement. You need to be tuned in to the other person and not just to yourself and what you might want to say.

This breakdown of the three types of conversations and the importance of alignment on the conversation you’re having reminds me of the book Thanks for the Feedback, which identified three types of feedback that you could receive: coaching, evaluation, and appreciation. The book highlights how important it is in a feedback conversation to be explicit about the type of feedback that’s needed in that moment.

As with the three types of conversations from Supercommunicators, you’ll need all three at different times, but in any given moment you’ll want to be on the same page about what type of conversation is taking place.

So let’s take a closer look at each of these types of conversations so that you can better identify them and navigate your way through them.

In a practical conversation, you’re figuring out what topics you want to discuss and you’re figuring out how that discussion will unfold.

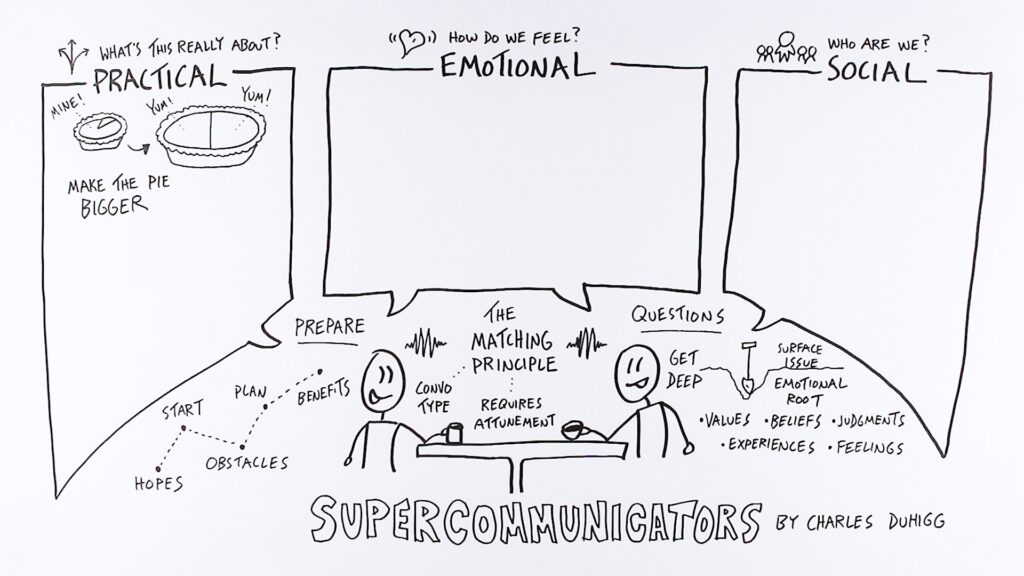

Practical Conversations

Here Duhigg brings in the field of interest-based bargaining: thinking of the conversation as a negotiation and looking for win win solutions that don’t focus only on you getting the biggest piece of the pie possible, getting just what you want out of the conversation, but instead making the entire pie bigger so that you each get out from it the thing that you need.

Prepare

You can make that pie bigger by following a handful of steps, some of which apply to multiple types of conversations, like the step of preparing before the conversation takes place.

Here you can ask yourself:

- What are your hopes for this conversation?

- How will you get it started?

- What obstacles might emerge based on the topics you’d like to discuss?

- If those obstacles appear, what’s the plan for overcoming them?

- If thinking about obstacles and making plans starts to stress you out a little bit, remind yourself what are the benefits of having this dialog?

The exploration of benefits is especially helpful when there’s a weighty topic that you’d like to discuss with someone else.

Ask Questions

Once the conversation kicks off, you’ll want to be ready to ask questions. Not boring ones that keep you on the surface, but instead open-ended questions that help you to get deep, so that you can get to the root (often emotional) ff whatever topic you’re there to discuss.

You can get to those deep questions by asking about someone’s values and beliefs. “How did you decide to ____?”

You can ask them to make a judgment. “Are you glad that ____?”

You can ask them about their experiences. “What was it like to ____?”

And you can ask directly about their feelings, which we’ll talk more about in the emotional section.

For now, though recognize that asking deep questions not only shows the other person that you’re interested in what they have to say, but they also get you to what’s most interesting about the topic that you’re discussing. They make the conversation more meaningful, for both parties.

Notice Clues

As you are asking those questions and listening to the responses, you then have the opportunity to notice clues. This is where attunement comes in.

Be on the lookout for indicators that the other person is engaged. Maybe they’re leaning in. Or they’re making eye contact. They’re smiling. Even interrupting (in an additive way) is a sign of engagement.

Also look for signs that they’re disengaged. They go quiet. Their expressions are passive. Their eyes are fixed elsewhere.

Experiment

If you notice those signs of disengagement, you can try adding something new to the table.

You could tell a joke or introduce a new topic or throw in a weird question.

Treat those as experiments. And then, as Duhigg writes, “Watch to see if your companion plays along.” Notice if you see signs of a shift toward engagement.

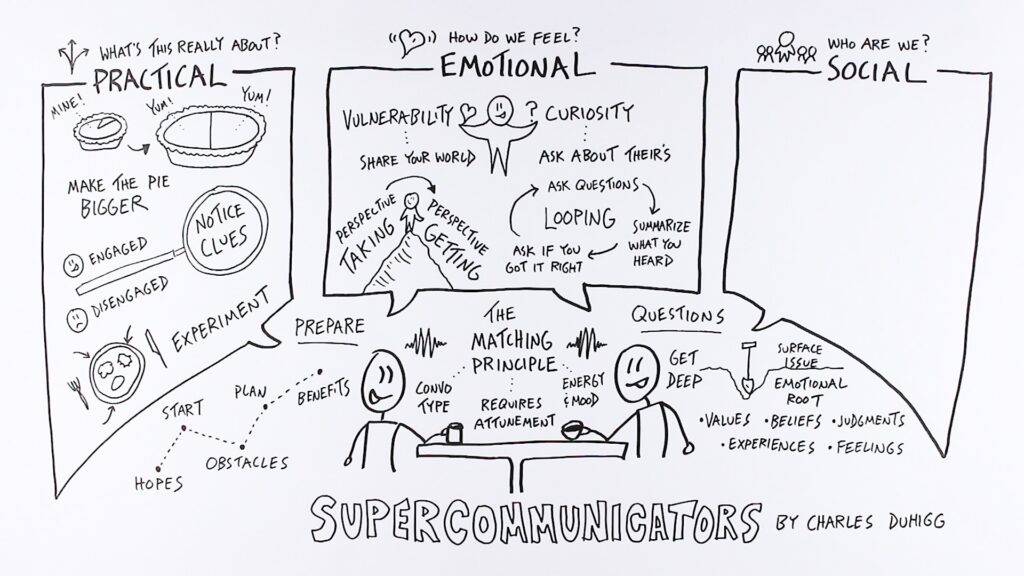

Emotional Conversations

Once you get into the conversation and get a sense for what it’s really about, you’ll likely transition into one of the next two types of conversations. Let’s now talk about the importance of discussing how everyone feels about the topic at hand.

Emotions are important because they allow you to get deep. As I mentioned, there’s often an emotional root that lives below the surface issue, that help you understand why you’re responding in the way you are.

Vulnerability & Curiosity

To engage successfully in an emotional conversation, you need to offer up two things: your own vulnerability and your curiosity.

You need to share your world and you need to ask about theirs.

It’s through that turn taking that you get to a level of depth and that you get to meaningful connection. It can’t just be a one way flow.

Perspective Getting

When emotions come up, it’s easy to think that we know where someone is coming from, or what precise emotion they’re feeling. And you might even do your best to take their perspective on the topic at hand, to see things from their point of view.

But Duhigg encourages us to move from perspective taking to perspective getting. Don’t take their perspective, ask them for it directly so that you’re not making incorrect assumptions.

There’s an example in the book of parents talking to their teenage son, saying, I” remember what it’s like to be 16. I know what you’re going through.”

Do you though?

Maybe you have a vague recollection of that stage of life, but you don’t know the precise way that your son is feeling, the specific things that he’s experiencing, and the varied ways that he is processing those experiences.

So instead of attempting to take their perspective, get it by asking for it.

Looping for Understanding

Here’s a concrete method for getting that perspective. It’s called looping for understanding.

It starts with asking a question and then listening deeply to what you hear. Then, instead of assuming you understand, you summarize what you heard back to the other person, and then you ask if you got it right, which gives the other person the opportunity to clarify.

By continuing that process, you give the other person the opportunity to clarify precisely what it is they want to say, and you give yourself the opportunity to make sure you understand and you’re not misinterpreting anything that you hear.

Looping plays a key role in another book that I’ve read and am excited to sketch out, High Conflict by Amanda Ripley. Duhigg references that book and talks about conflict directly here in this section, because it’s within the context of a conflict where looping for understanding is especially important. As Duhigg puts it, “We learn why we are fighting by discussing emotions. We draw out emotions by proving we are listening. And we prove we are listening by looping for understanding.”

While in that process of looping, the matching principle comes up again, this time the importance of matching energy and mood. Because while it’s difficult to predict the exact emotion that someone is feeling just by looking at them, you can tell where their energy and mood is at.

Is their energy high or low? Is their mood positive or negative? And you can match that, or at least acknowledge where they’re at as a way of showing that you’re listening and that you’re connecting with what they’re bringing to the table.

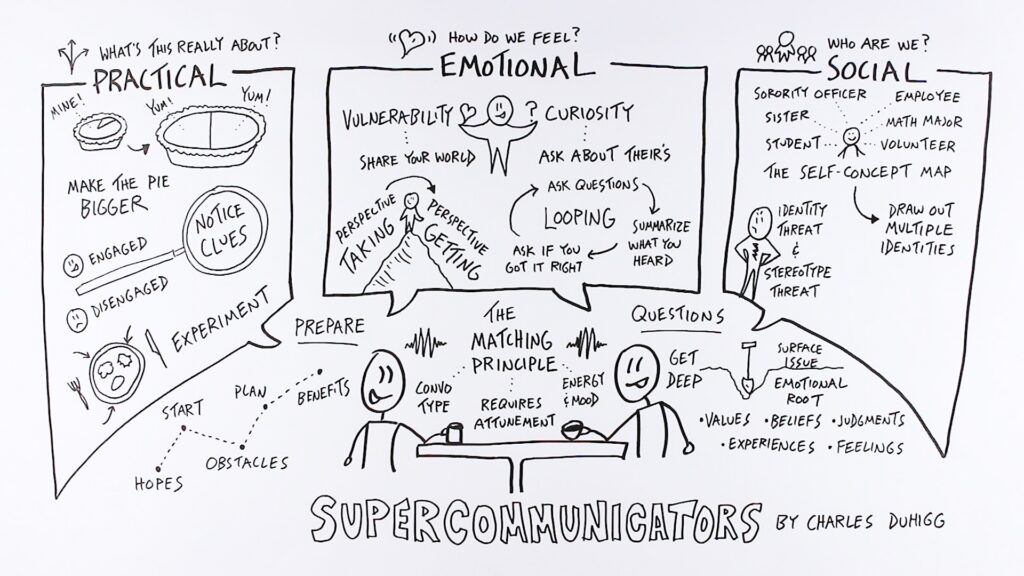

Social Conversations

So emotions help us discuss and understand our responses to specific events. But you can get to something even deeper when you explore the identities that are present underneath those emotions. That’s what the social or “Who are we?” conversations are all about.

The Self-Concept Map

Notice that I said identities with an “s” at the end. You are more than one thing, and so is everyone else that you ever interact with.

An example from the book shares someone who is a student, and a sister, and a sorority officer, and an employee, and a math major, and a volunteer (among many other things).

Some of those are social identities, which are about how we see ourselves and believe others see us as members of various tribes. Others are personal identities, how we think of ourselves apart from society.

Identity & Stereotype Threat

While identities are always important, they tend to come to the surface when one of them is challenged. Duhigg identifies two different types of threats that can occur: identity threats and stereotype threats.

Identity threats (which also showed up in Thanks for the Feedback) result when something negative is said about a group that you belong to. In response to an identity threat, we often become defensive and then make some sort of counter attack, which often takes the form of saying something negative about a group that the other person belongs to.

Then you get into a vicious cycle. As Duhigg puts it, “These threats are deeply corrosive to communication.”

Stereotype threat is a bit different. This is something that can undermine your performance with the mere existence of a stereotype around a group that you belong to.

One example is the stereotype that women aren’t good at math. If you’re a woman and have been exposed to that stereotype, even if you’re in a setting where the people around you don’t believe it, the mere existence of that stereotype can cause you to second guess your answers on a test and lose valuable time and waste mental processing power in the process.

But there’s a way to combat stereotype threat and also reduce identity threat, which involves the drawing out of your multiple identities.

A study found that when individuals created their own self-concept map, one that had as many nodes as possible (where you list out all of your identities) — that was effective in reducing stereotype threat because it reminded you of other aspects of your identity where that threat doesn’t exist. It boosts your overall sense of self and your general confidence, which then reduces the second guessing that might occur during a given performance.

It can be an antidote to identity threat. When two people in a conversation each sketch out their own self-concept map and share it with each other, they’re likely to find connections across some of those identities, even when there are significant conflicts between others.

By locating and speaking to those connections, you’re more likely to see the other person in a more complex way and not reduce them down to that one topic you disagree about. This supports a more meaningful dialog.

This self-concept map came up under a different name in the book What Works by Tara McMullin, where she describes the idea of the network self (from philosopher Kathleen Wallace). The practice is similar (list out your various identities) but the purpose is different (decide which of those identities you’d like to lean into in the coming months).

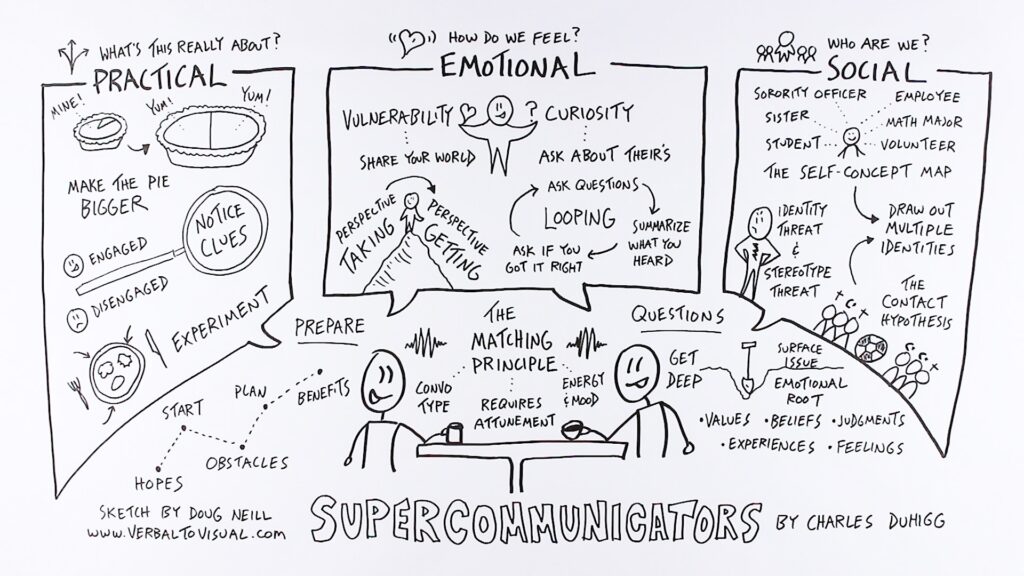

Putting It Into Practice

Duhigg tested these ideas in Qaraqosh, Iraq, within a soccer league designed to break down barriers between the Christian and Muslim communities. The league required a mix of players from each group, putting the contact hypothesis to the test.

The contact hypothesis posits that if you bring people with clashing social identities together under certain conditions, you can overcome old hatreds. One of the most important conditions: everyone must be on equal footing.

In this case, it worked. Those soccer players were nudged to think about identities beyond religion: identities around position (goalkeeper, forward) or around roles on the team (the person who leads stretches, the person who brings drinks). At the same time, they formed a new in-group as members of that team.

They found that those connections transcended beyond the soccer field, with Christian and Muslim team members sharing meals together and hanging out outside the context of soccer.

It didn’t solve everything though. There was still a sentiment of “You’re one of the good ones, but I still don’t trust those other Christians.” But among those participants, at least, the drawing out of multiple identities supported meaningful connection where previously there was just hatred.

A Framework for Connection

What I appreciate about this discussion of the types of conversations is that they can be applied to conversations with loved ones we’ve known for years as well as strangers we just met. They’re helpful in lighthearted conversations and in deep, difficult conversations, some of which occur across social divides.

Let’s circle back to that Harvard Study of Adult Development: the most important variable to being happy and healthy is how satisfied you are in your relationships. And those relationships are kept alive via long and intimate discussions.

These principles help you make those discussions meaningful.

If you enjoyed this exploration of ideas from Supercommunicators, I encourage you to pick up the book and give it a read. And if you’re interested in developing your visual thinking skills to create your own sketched summaries of the books you’re reading, check out The Verbal to Visual Curriculum.