In her book What Works, Tara McMullin encourages us to change the way we approach goal-setting.

She explores how the traditional ways of approaching goal-setting might be wrapped up in the wrong stories and the wrong systems, stories and systems that don’t work for a large portion of society.

I’d like sketch out some of my favorite ideas from the book and share a bit about how I’m applying them to my life and work.

If you like what you see, I encourage you to go grab the book for yourself.

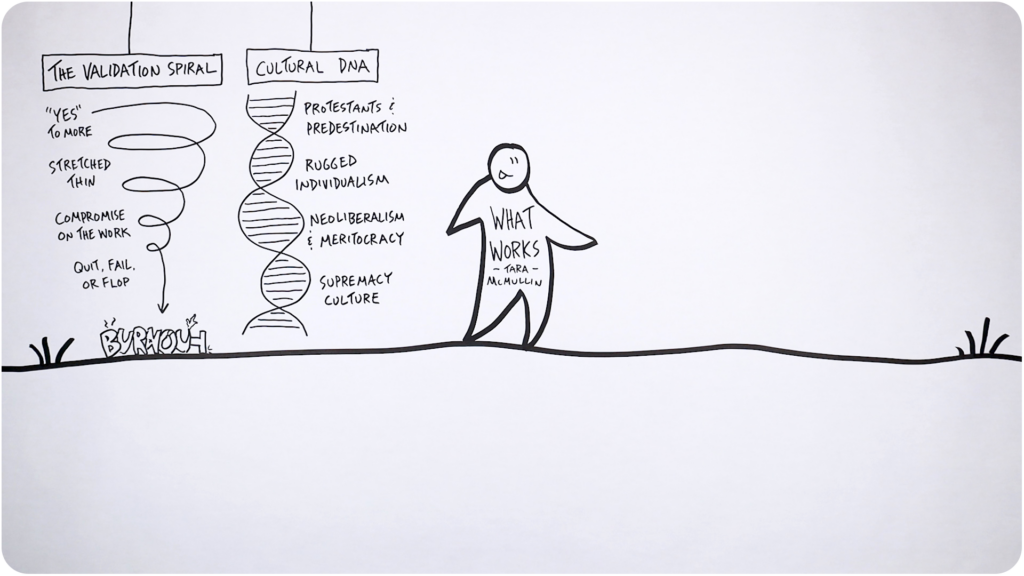

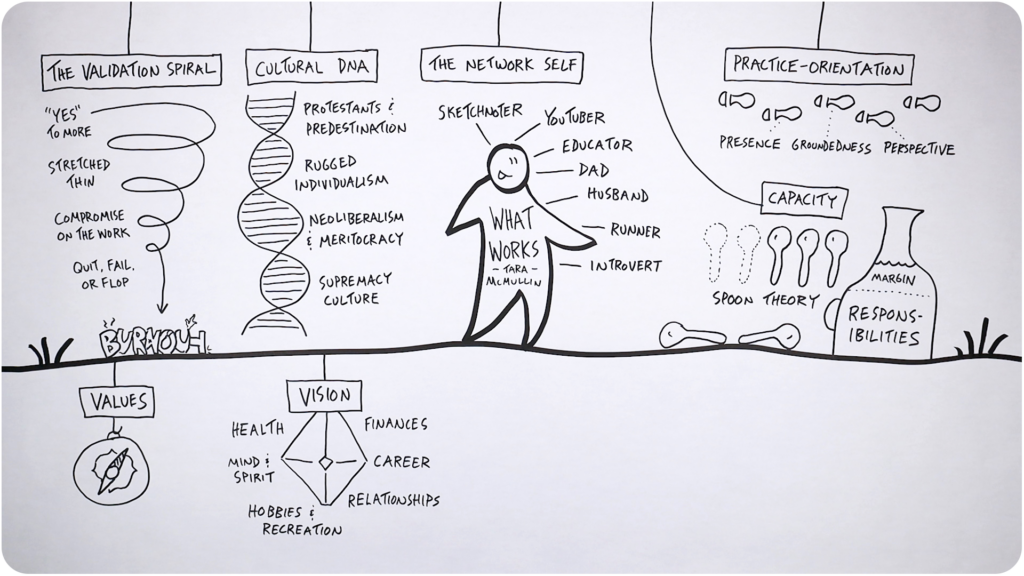

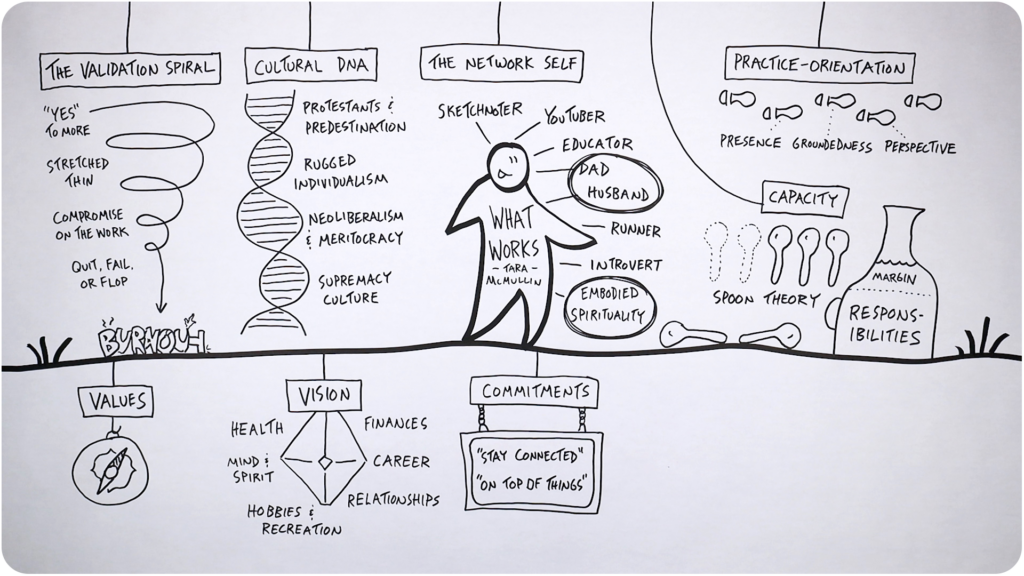

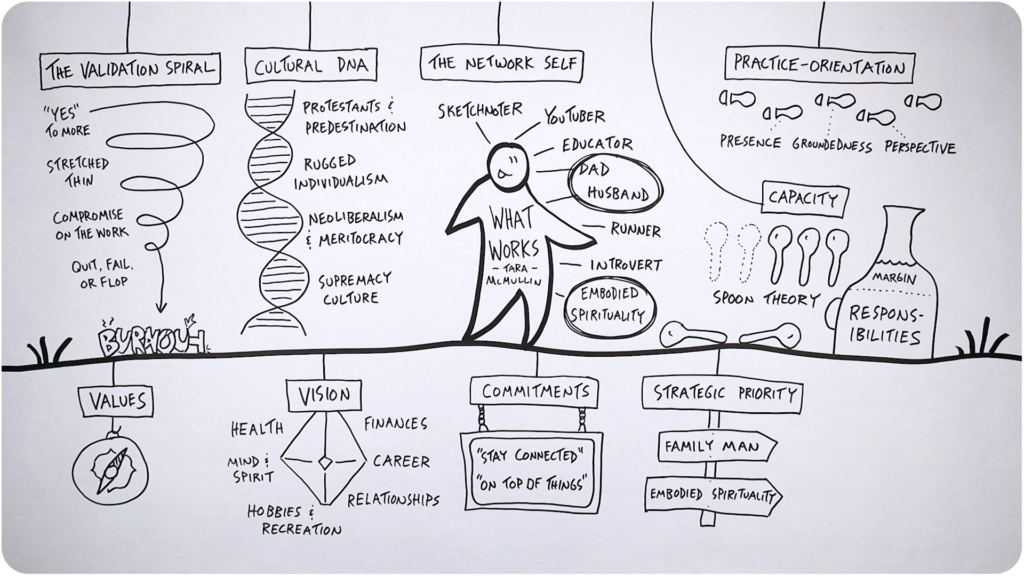

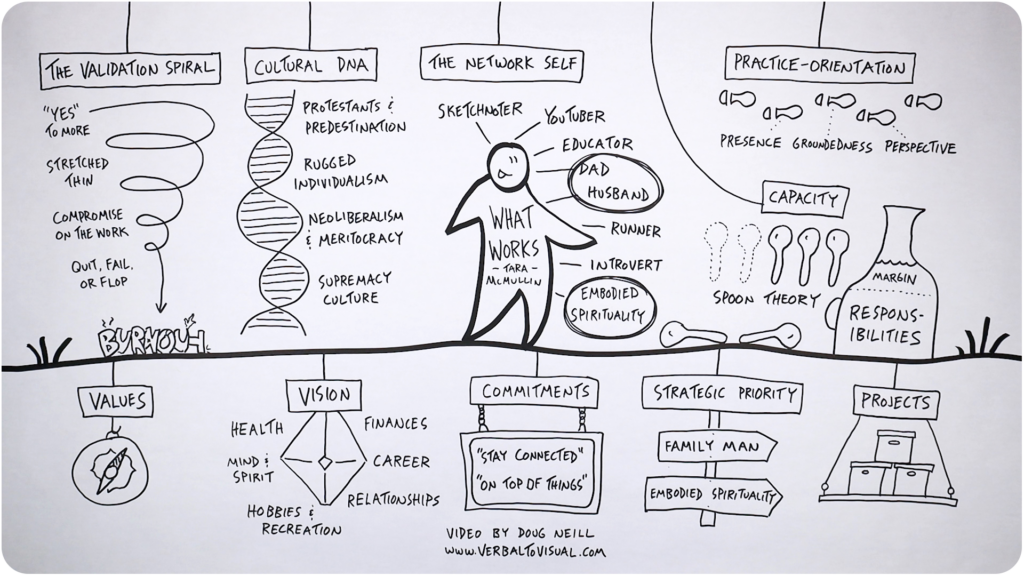

The Validation Spiral

One of the potentially unhealthy aspects of goal-setting is how closely it can be tied to external validation. The desire for validation is what fuels the validation spiral, one of the early concepts that McMullin introduces.

The spiral starts when you say yes to more and more responsibilities in order to prove yourself to others or acquire more quickly what you don’t yet have. But all of those yeses lead to your resources being stretched thin – there’s simply not enough of your time and energy to go around.

Because of that, you then have to compromise on the work, giving less attention than would be ideal to each of the various tasks you’ve agreed to. Over time, all of that compromising often leads to you quitting, failing, or flopping on some or all of the projects that you’re trying to take on.

That ultimately leads you to burnout, when you’re mentally, physically, and emotionally drained. It’s often a goal that you’ve set for yourself (explicitly or implicitly) that fuels the spiral and leads to the accumulation of both psychological and physiological stress that wears your body down.

Here’s the thing, though: that validation spiral that many (if not all) of us have experienced – that’s not innate to us as human beings. It’s the byproduct of the culture that we live in.

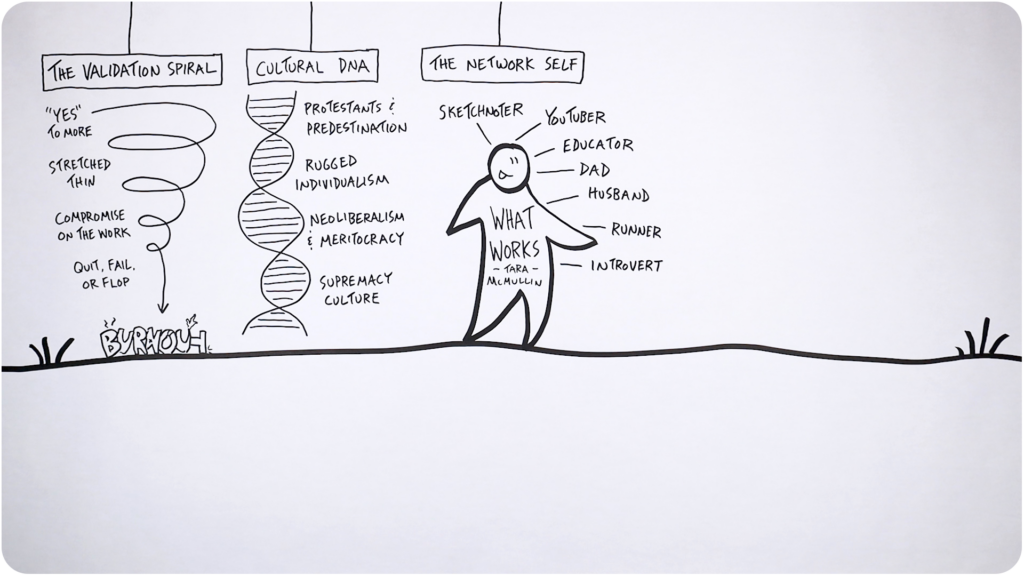

Cultural DNA

Here McMullin introduces another spiral, this time the cultural DNA that has shaped how most of us in the western world experience life.

This is where McMullin does an interesting deep dive into the roots of the culture of the United States in particular that sheds a lot of light on how we approach careers and success and life in general.

She goes all the way back to the Protestants who founded the country and explains how their belief in predestination led to an ethos of individualist hard work, because it was believed that material success was an indicator that you’re one of the chosen ones, and that gave you moral superiority over others.

Those beliefs influenced the rugged individualism that Herbert Hoover talked about in a speech in 1928, where your health and wealth is your responsibility alone, therefore removing responsibility from society. As McMullin points out, the thing about individualism is that it doesn’t work when there’s not equality of opportunity, which definitely didn’t exist in 1928 and still doesn’t exist today.

That idea of rugged individualism went on to influence the policies of neoliberalism based in a supposed meritocracy and the rule of the free market. Even though there’s plenty of evidence showing that free markets don’t create a level playing field, that concept is still pretty ingrained.

What those elements of cultural DNA result in is an extreme burden on the individual, regardless of their circumstances.

On top of all of that individualism, there’s also supremacy culture to deal with, which are the norms that result from believing that one group is better than another group. Supremacy culture is the reason that for women it’s more beneficial in the workplace to act more male, for black people to act more white, for people in the LGBTQ community to act more straight and cisgender.

What results is a system where success comes through conformity and where difference is something to be overcome.

That’s a messed up system that doesn’t work for a whole lot of people. And it’s a system that misses out on the contributions of a whole bunch of interesting identities.

It’s the exploration of identity that we turn to next.

The Network Self

McMullin acknowledges that we all contain multiple identities by bringing in the concept of the network self from the philosopher Kathleen Wallace, which encourages us to acknowledge and appreciate the various components of our identity.

Some of my own identities include sketchnoter and YouTuber. I’m an educator. I’m a dad and a husband. I’m a runner and I’m an introvert, among many other things of course.

This exploration of your own multiple identities and tying that to your whole approach to goal-setting was one of the most impactful things for me from this book.

McMullin points out that because of the cultural DNA that is immersed in us, oftentimes we seek out new identities simply to increase our market value, not because they’re actually true to who we are.

But what if you dropped those identities? What if you got rid of the ones that came from cultural influences and not from yourself. That’s a question that we’ll come back to when we look at the explicit framework that McMullin outlines.

Before that, though, there are a few more important foundational pieces to explore.

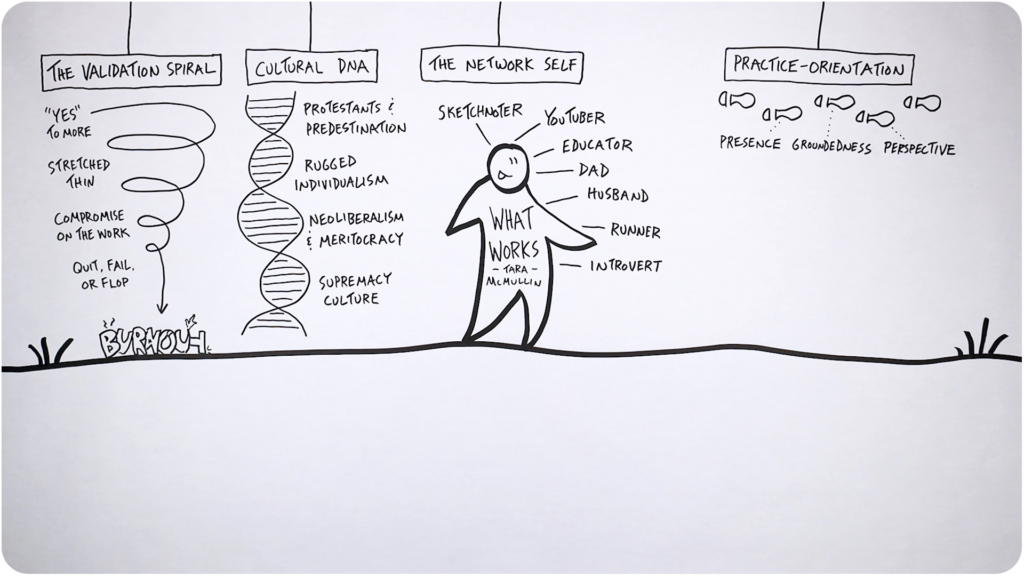

Achievement Orientation vs Practice Orientation

We live in an achievement-oriented world, where we’re constantly being encouraged to set and then reach new goals.

That hints at one of the reasons goals can make us miserable – they’re designed to end. Either you fail at achieving it, which doesn’t feel good, or you do achieve it but then you just have to move on to the next goal. There’s no lasting sense of satisfaction that comes from that achievement orientation.

You do get that satisfaction, though, with a practice orientation.

I love how McMullin highlights that it’s not about practice makes perfect – the purpose isn’t reflection or even improvement. Instead, the purpose of practice is presence, groundedness, and perspective. That’s what leads to a deeper sense of satisfaction in your daily activities.

But as we start to think about our daily lives and how exactly we spend our time, we need to talk about capacity.

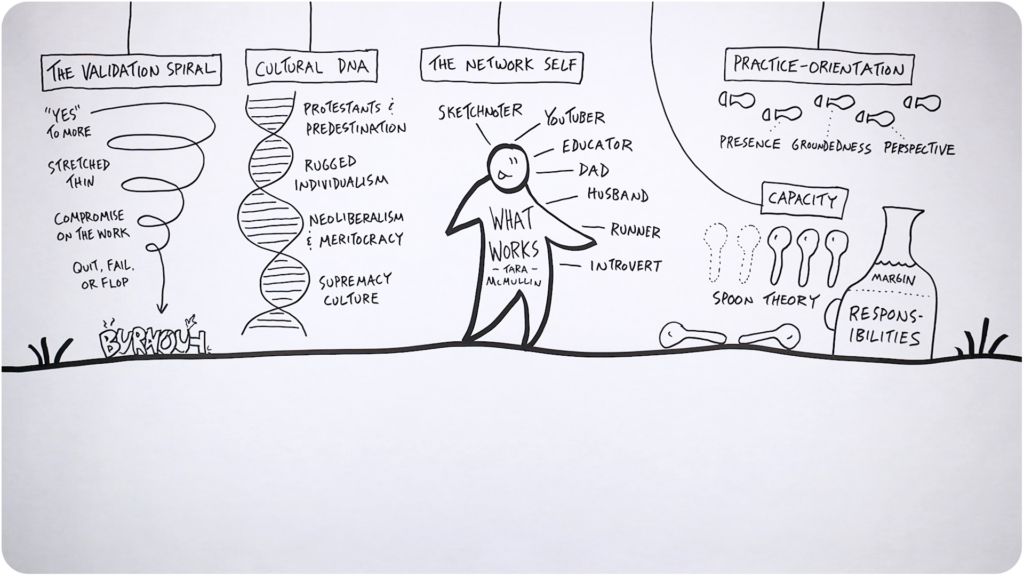

Capacity

McMullin defines capacity as “the extent of what you can do with the resources you have access to without burning out or breaking down.”

She acknowledges that everyone has a different capacity, bringing in the concept of spoon theory from Christine Miserandino, which posits that we all start the day with a certain number of spoons, but we have to give one up for each strenuous task.

For some people, getting out of bed and getting dressed is a strenuous task and requires a spoon. For other people, going to the grocery store is a strenuous task that requires a spoon. Some people face oppressive systems at work or just out in society – those can add up to another spoon down.

McMullin points out that these limitations aren’t a matter of mindset or positive thinking. They’re due to things like being confined to a wheelchair or simply being neurodivergent living in a world that’s not built for how your mind works.

While it’s important for us to work toward a world where the environments we create are well-suited for a more diverse set of identities, it’s also important for each of us to take stock of our own personal capacity so that when we decide what responsibilities we’re going to take on, we have a realistic sense for what’s not going to burn us out and we can build in some margin to give ourselves some breathing room.

With those foundational elements that explore the role of society and the role of self, we’re now ready to dig in and make use of the specific goal-setting framework that McMullin proposes.

Identify Your Values

One potential difficulty that might arise after acknowledging and then dropping some of your cultural DNA is that there can be a feeling of lack of direction after leaving individualism and achievement-orientation behind.

That’s why it becomes important to explore and identify your own values, which can serve as a compass for you as you make decisions about how you want to spend your time.

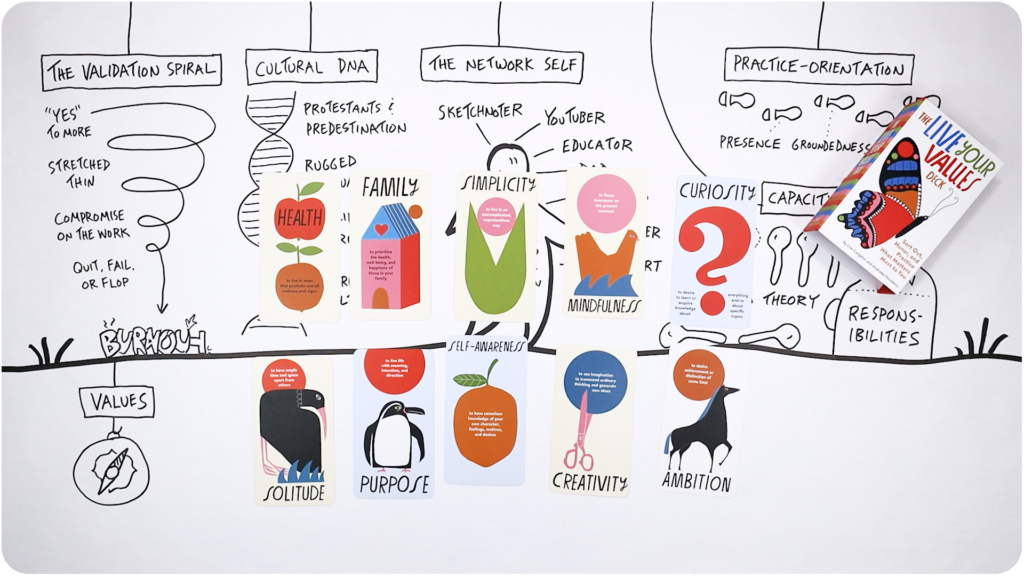

This is where I brought in the work of an illustrator an author who I admire, Lisa Congdon, who along with Andrea Niculescu created The Live Your Values Deck, which is a set of beautifully illustrated cards, each of which identify a value with a brief description, and on the back ideas and suggestions for how you might live out that value.

You can find similar lists of values online, but it’s nice to have some tactile cards with beautiful illustrations as you’re identifying what values you want to place top of mind right now.

The image above shows the values that are important to me right now, which is probably on the higher end as far as the number of values to try to focus on (I think McMullin encourages you to get down to three).

Once you’ve identified your values, you can turn next to the vision of the life that you’d like to create for yourself.

Craft Your Vision

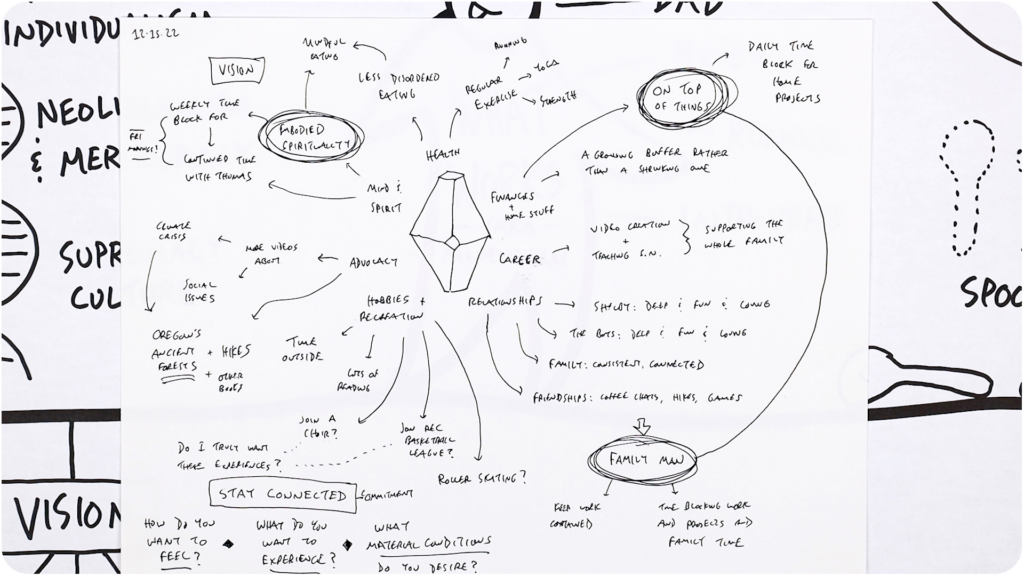

As you start to craft a vision for your future, McMullin encourages you to think about various dimensions of your life, from your health to your finances, your career and relationships, your hobbies and recreation, your mind and spirit, as well as advocacy.

Look at each of those components of life and think about how you want to feel in one year or five years or ten years? What do you want to experience? And yes, what material conditions do you desire?

This is what it looked like when I explored those various dimensions:

What this exercise helps you to see is where there’s potential for you to start taking on new identities, or perhaps just lean into aspects of your identity that have been neglected.

In my case, I recognized that even though I’ve been a dad for a little while now (I’ve got twin boys who turn two years old in a couple of months), the identity of father and family man is one that I want to continue leaning into, especially since at various stages of my life individualism had a fairly strong hold.

Over the past year I’ve also been pulled into the world of embodied spirituality, which is an approach to your inner life and relational life that has a lot in common with practice orientation. It’s about presence and groundedness, maintaining a connection to what’s going on inside of your body and not just your brain. That’s a newer component of my identity that I’d like to continue exploring.

With a vision for your future crafted, and perhaps a couple of specific identities to focus on, you can start making some commitments.

Make Commitments

The commitments that you choose to make are a replacement for achievement-oriented goals.

Goals are focused on results that might come in the future. Commitments are focused on growth that can be achieved in the present.

One of the commitments that I’m making right now is to stay connected – to others as a father and a husband, and to my body as I explore embodied spirituality.

I’ve also identified a commitment to be on top of things, from simple housekeeping tasks to car maintenance to finances. There have been many periods of my life where I haven’t felt on top of things, which carries with it a weight that I’d like to not have on my shoulders.

With a few commitments in place, next we move on to strategic priority.

Set Your Strategic Priority

This is where you identify your designated focus for a period of time.

Here McMullin brings in a mountain metaphor, where the top of the mountain is a new identity that you’d like to embody, acknowledging that there are a variety of paths that can get you to that peak. Your strategic priority is the path that you choose to take, for now at least.

I am choosing to follow the path of the family man and the path of embodied spirituality.

Where your commitments are about putting one foot in front of the other, your strategy is about the choice of the trail you go on and the outcome that it leads you to.

Once you’ve identified your strategic priority, you then get to choose which projects to take on that will help you fulfill that strategy.

Define Your Projects

The important thing about projects is that they have a clear scope and outcome, and take somewhere around four to eight weeks to complete.

McMullin identifies three types of projects:

Closed loop projects are over and done once you’ve completed them.

Open loop projects are smaller chunks of one big project, something that maybe takes six months that you break down into smaller chunks to have some milestones to work toward.

Routine projects help you to establish a new routine, habit, or system that you’ll continue with even after you mark the project as complete.

As I heard McMullin talk about some of the yearly planning that she does and how she identifies some specific projects that she’ll work on in each quarter of the year, I decided to try that out for myself. I’ve never attempted to plan for a year in advance, quarter by quarter, but I found it to be a very useful exercise.

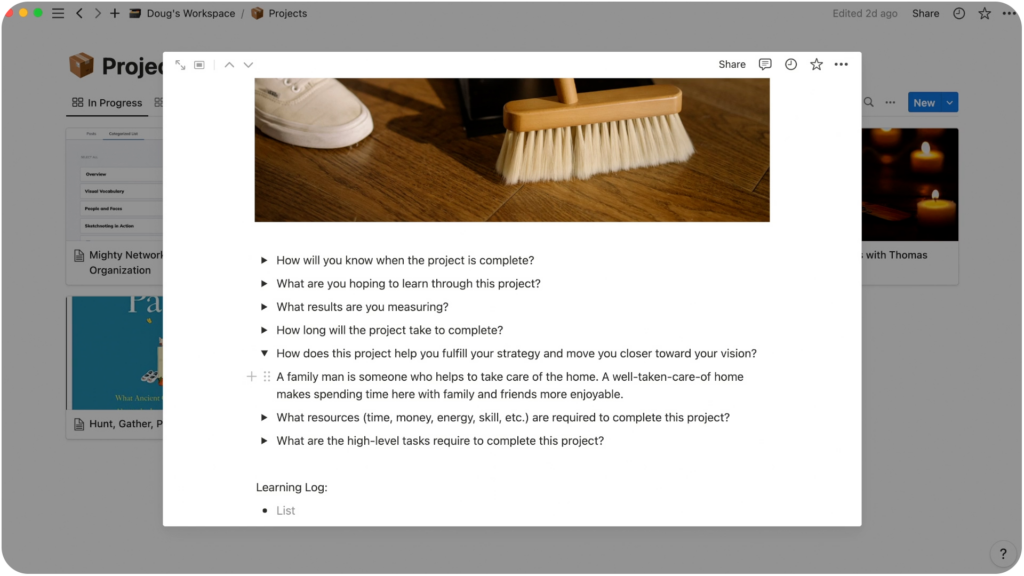

I use Notion to keep track of those projects, which is also where I keep a project brief that has specific prompts that McMullin introduces, like how will you know when the project is complete? What are you hoping to learn through this project? What results are you measuring? How long will it take?

It’s a pretty quick exercise to respond to each of those.

With my project of building out a housekeeping database, the connection to strategy I described in this way: a family man is someone who helps to take care of the home, and a well-taken-care-of home makes spending time here with family and friends more enjoyable.

So that project helps me live into the identity of family man and someone who’s on top of things.

Within the realm of embodied spirituality, I enjoy the work of Thomas Hübl who hosts a gathering called The Mystic Café every month, which includes some meditations and some teachings that I’ve found to be valuable. I spend time with those each Friday and Saturday morning.

It’s through projects that you can start to bridge the gap between the values you’ve identified for yourself, the vision for your future, and the day-to-day activities that you actually spend time on.

The projects aren’t set in stone. There’s plenty of flexibility and the opportunity to respond to new situations as they arise.

But in general, this activity of identifying which projects I’d like to focus on in each quarter of the year helps keep that capacity piece in check, to ensure that I’m not over-committing myself.

I think it makes it easier to lean into practice orientation as well. Since I’ve got projects dedicated to each important area of my life, that makes it easier to focus on the thing that I’m working on right now, to give it my full attention.

As you can probably tell, there’s a whole lot from this book that resonated with me, and there are plenty of ideas that I didn’t even have time to mention here.

So if you enjoyed this overview, I encourage you to pick up the book for yourself.

And if you’re intrigued by the visual component of this summary, that happens to be a skill that I teach.

It’s called sketchnoting, and inside of Verbal to Visual you’ll find a whole library of courses as well as a vibrant global community of visual thinkers that will help you develop this skill and apply it to whatever work that’s important to you.

If that sounds interesting, come check us out.

I’ll be back again soon with another visual book summary.

Till then,

-Doug