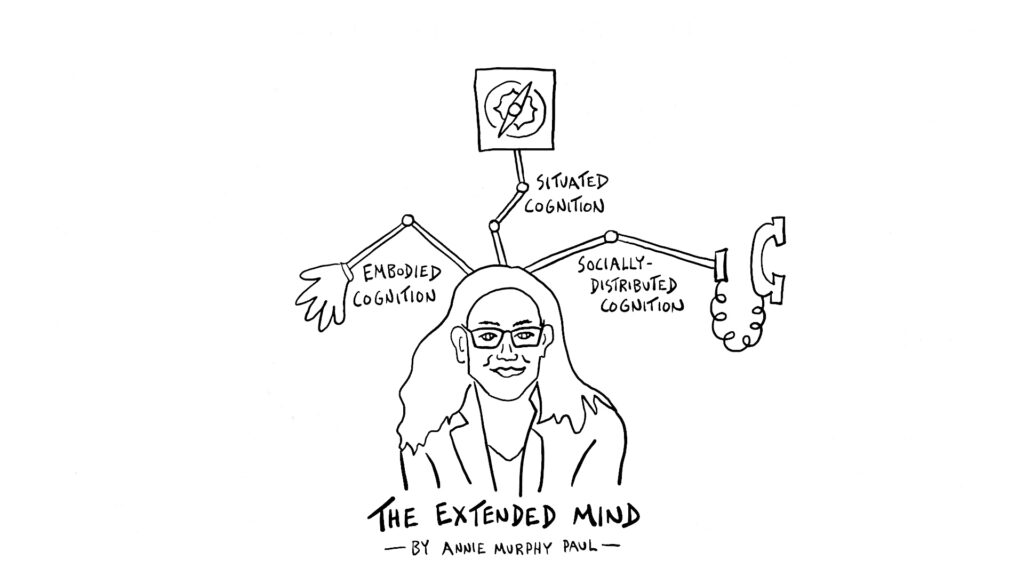

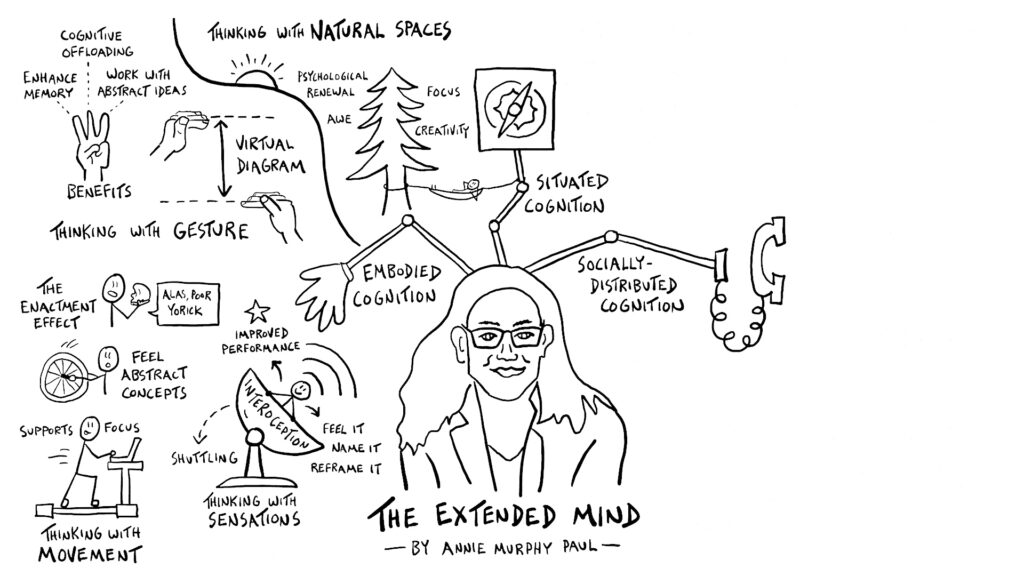

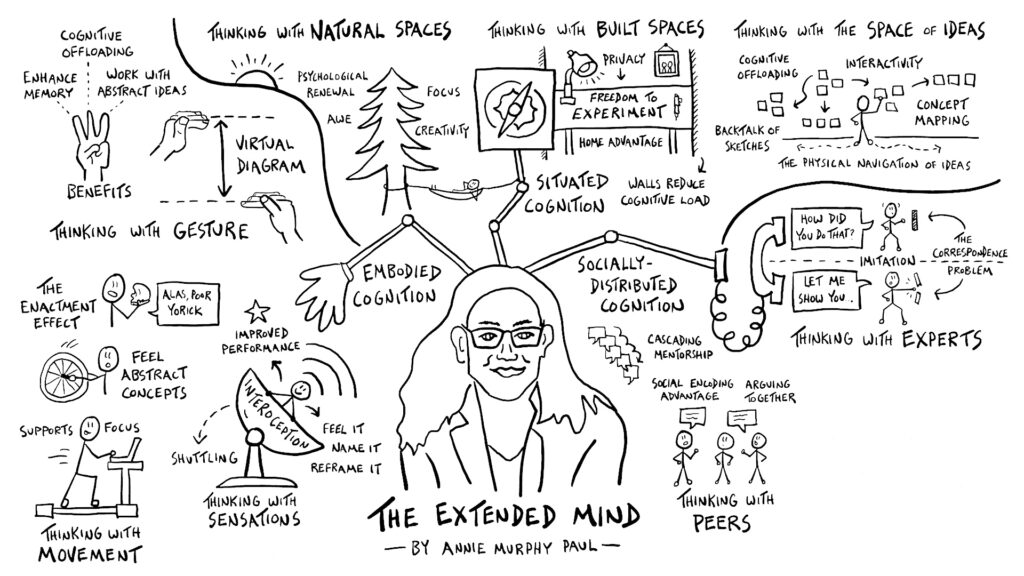

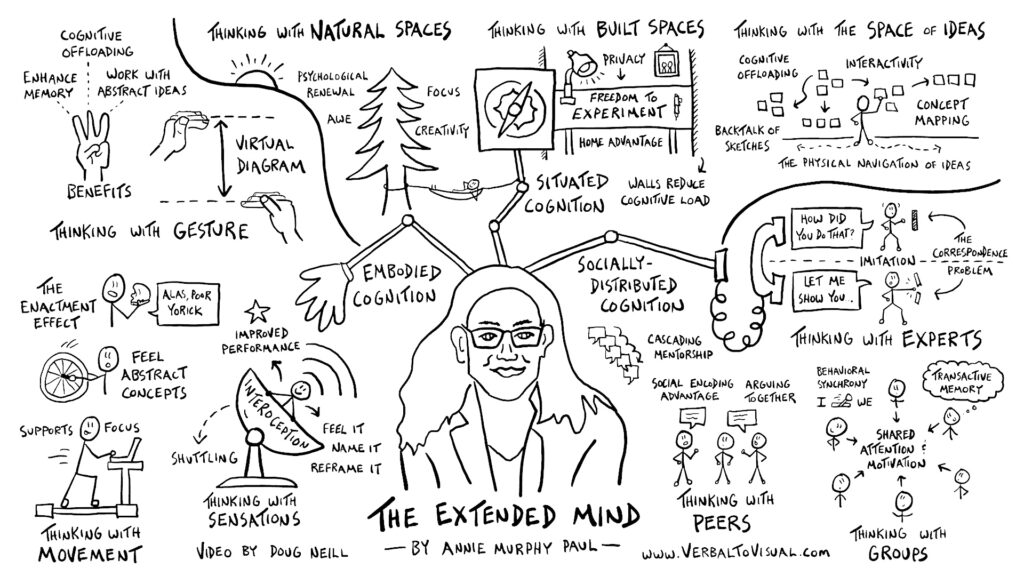

In her book The Extended Mind, Annie Murphy Paul explores the power of thinking outside of the brain – how we use resources outside of our heads that help us to think better.

In the video above and article below I would like to sketch out some of my favorite ideas from the book, which is broken down into three sections.

The first section explores embodied cognition – how we think with our bodies; the second, situated cognition – how we think with our surroundings; and the third, socially-distributed cognition – how we think with our relationships.

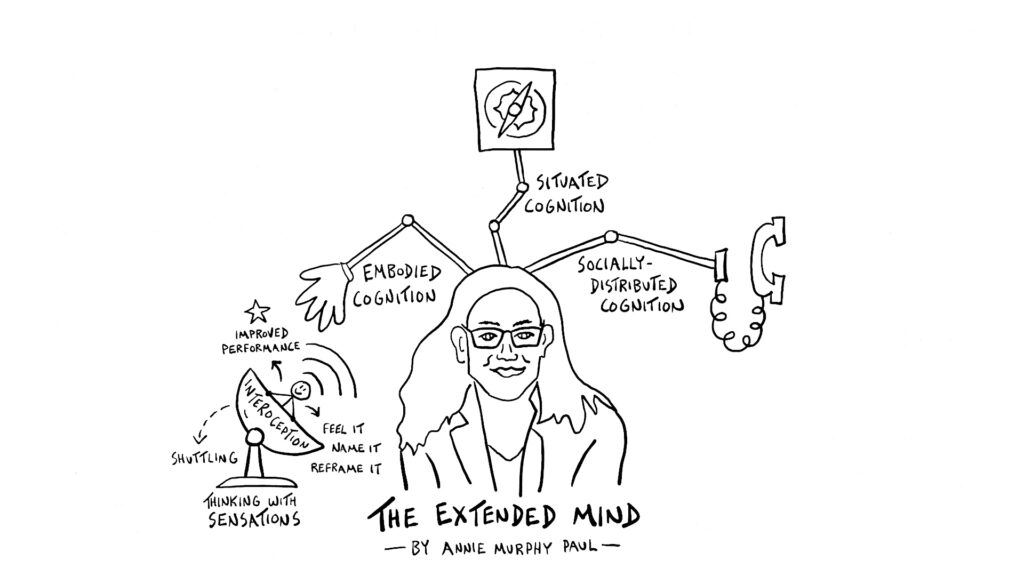

Thinking with Sensations

Let’s start with embodied cognition.

What Paul describes first in this section is how we can think with sensations by paying attention to how our body feels. That particular skill, that awareness of the inner state of your body, is called interoception, and it’s a little bit like thinking of your body as radar, regularly monitoring what’s going on inside of your body.

What’s interesting to note is that interoception is actually linked to high performance. One example given was stock traders, of all people. Those traders that were more in tune with their body made better trades, the explanation being that they were quicker to notice feelings of intuition in response to what was going on in the market.

The skill of interoception tends to be relevant in games or experiences that require noticing patterns, because often your body and unconscious mind notice a pattern before it enters your conscious awareness. So the more in tune you are with your body, the more likely you are to notice those signals.

Interoception also plays a role in emotional regulation. When you pay attention to how your body is feeling, you’re more able to go through this process of cognitive reappraisal – where you feel the feeling, name it, and then potentially reframe it (if the default interpretation isn’t particularly constructive).

Here Paul also brings in the idea of shuttling, where you move your focus back and forth between what’s happening inside of your body and what’s going on outside of your body, noting how beneficial it can be to regularly tune into both of those sets of stimuli. You gain some understanding when you pay attention to what’s going on outside of you, and then a different understanding when you listen to what’s going on inside, which can give you a more holistic perspective on whatever is going on.

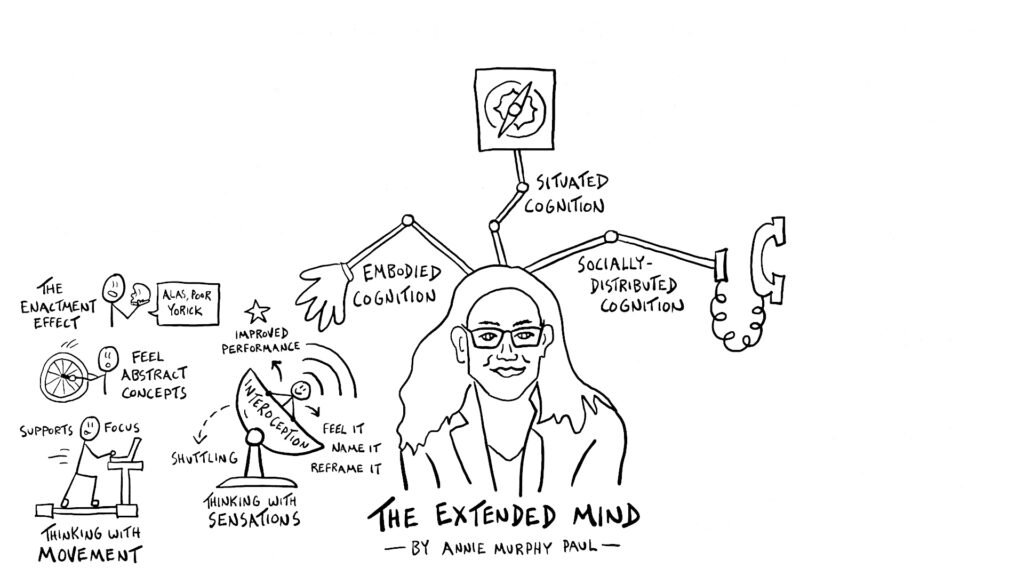

Thinking with Movement

Next we turn to thinking with movement. We’ve got these bodies that are designed to move, and it turns out the more we incorporate movement into our days, the better we’re able to think.

One interesting example in this chapter is a treadmill desk, where you combine a standing desk with a treadmill so that you can get some work done not just standing up instead of sitting down, but also moving. And as it turns out, that supports focus, particularly with visual tasks.

As someone who enjoys getting out of the house and going on long walks, I was pulled to this idea right away. I ended up getting a really simple treadmill that I placed up against a wall and added a shelf above it for a desk. I’ve gotten a lot of email and video editing and reading done while walking, and I’ve been surprised at how much cognitive momentum, and even creative momentum, can come from that relatively simple physical momentum, even though you’re just walking in place.

Another way that you can think with movement is by feeling abstract concepts. For example, in a physics class, you can get a literal feel for torque by holding a bicycle wheel, getting it spinning, and then tilting the axle from horizontal to vertical and back.

Actors also think with movement by connecting specific components of the staging of a scene to the lines that you need to memorize. This is called the enactment effect, where you connect specific movements to specific information that you’d like to recall, in this case the lines that you need to recite. That’s why some actors don’t even start memorizing lines until the staging of the scene is in place.

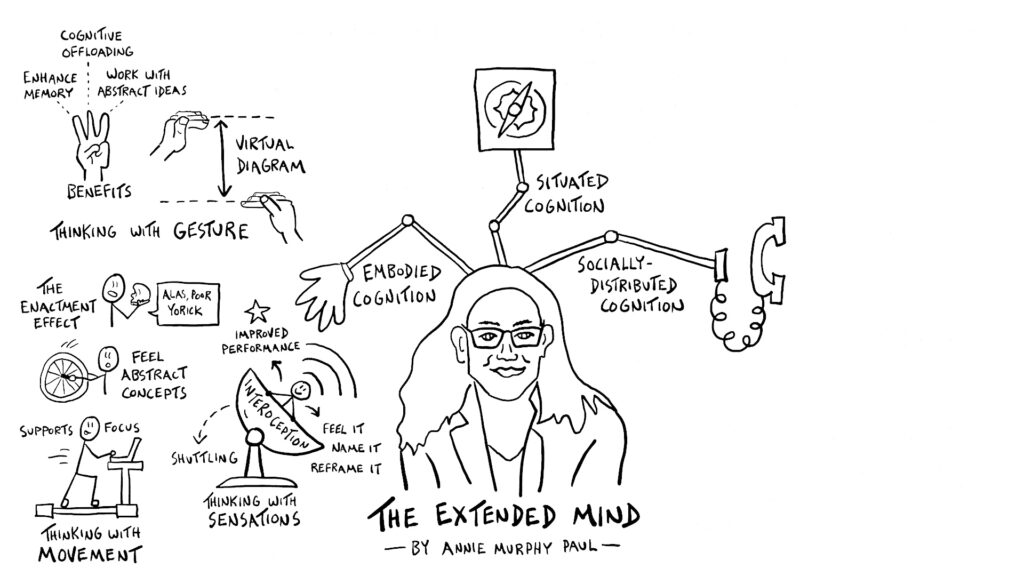

Thinking with Gesture

And it turns out you don’t even need to get your entire body involved in the process. You can actually do quite a bit of thinking with gesture.

The use of hand gestures while talking or even just thinking has three benefits. It enhances your memory because of the fact that you’re creating a stronger memory trace in your brain when you engage your body, your hands in particular in this case.

It also provides the opportunity for some cognitive offloading. The gesture that you’re making gives you a reference point to hold some of the information about what you’re describing, so that you don’t have to keep all of that in memory, even if it’s something as simple as reminding yourself that there are three main points that you’re making right now, you’re on the second, and you’ve got one more coming.

They’ve also found that gestures help you work with abstract ideas, because when you get your hands involved in the process, you intuitively start to create representations that give some form to the ideas that you’re working with.

One way that was described is as a virtual diagram – something that you create on the fly with your hands that provides an extra layer of context to the ideas that you are talking through or thinking through.

Thinking with Natural Spaces

Next let’s turn to situated cognition, which is all about thinking with our surroundings. It likely won’t surprise you that thinking with natural spaces is one of the environments worth considering. At the same time, I feel like nature is an underutilized resource when it comes to better thinking and better creative work, especially for those of us who live in an urban environment where it might be a little more challenging to get to natural spaces.

One of the benefits of spending time in nature is psychological renewal – the way in which nature helps us to relieve our stress and reestablish our mental equilibrium, both of which support better thinking. An increased level of focus is another benefit.

When out in nature you’re also more likely to experience awe, the feeling of amazement and wonder that often comes along with nature’s vastness, like “the unfathomable scale of the ocean, of the mountains, of the night sky” to quote Paul. When experiencing awe we become less reliant on preconceived notions and stereotypes. We become more curious and open-minded and more willing to revise and update our mental schemas – the templates we use to understand ourselves and the world.

We’re also more creative in nature. We engage in more imaginative play, we’re more receptive to unexpected connections and insights, and we tend to let our mind wander and follow our thoughts wherever they lead.

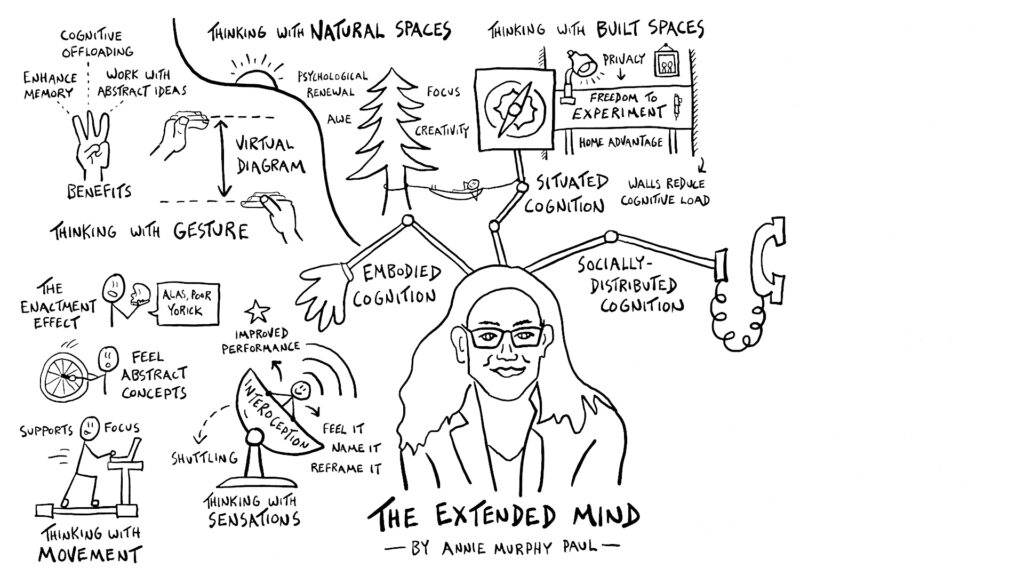

Thinking with Built Spaces

As great as natural spaces are, it turns out that human-built spaces also provide some benefits.

Even something as simple as a wall. When walls are put up that separate you from the potential noise and stimuli and other people outside of those walls, that actually reduces your cognitive load so that you can bring more focus and attention to the task at hand.

The privacy that comes within a walled space also has the benefit of giving you more freedom to experiment in ways that you wouldn’t if you knew that someone could walk by and take a look at what you’re working on.

Within a space that you have designed there’s also a home advantage – there are positive psychological benefits when you’re in a space that feels like your own, that has reminders of your identity, your goals, and your values. That home advantage leads you to feeling more confident and capable. It also makes you more efficient and productive.

Paul points out here that it’s not about spending all of your time in a private isolated space, instead suggesting intermittent collaboration, where you cycle back and forth between some sociable interaction and some quiet focus time.

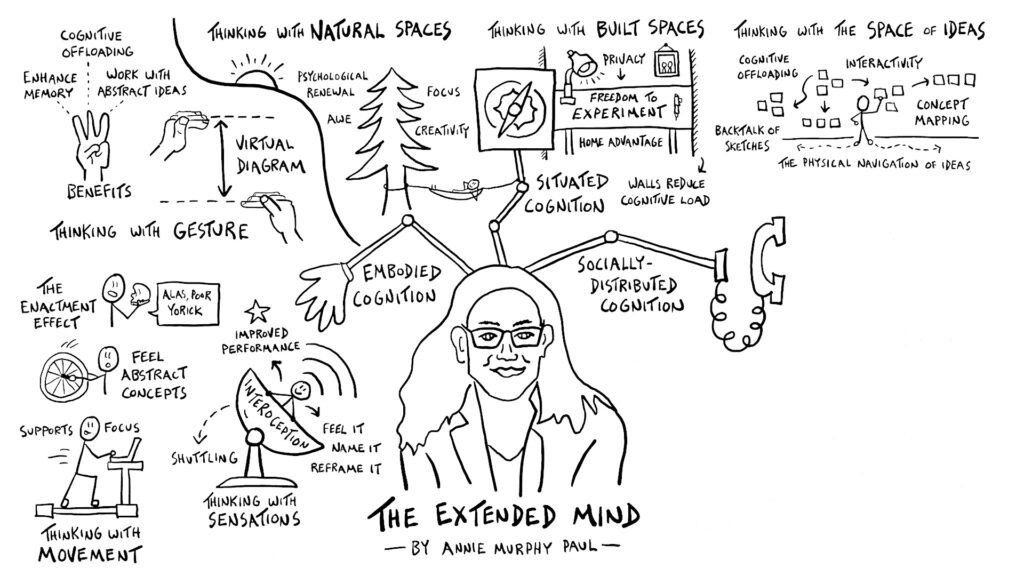

Thinking with the Space of Ideas

Next we move to thinking with the space of ideas, which was one of my favorite sections because it speaks the most directly to my interest in sketching out ideas and the benefits of creating artifacts that you can work with and move around as you’re thinking through some challenging material.

When you choose to sketch out ideas, perhaps by using sticky notes that you can move around on the wall, you get the benefit of cognitive offloading because you’re creating an external representation of an idea that you don’t have to hold in your mind, a benefit that we also saw of thinking with gesture.

You also get an interesting backtalk of sketches. When you give an idea some visual form on the page, it will talk back to you and prompt ideas for where you might go next, or maybe even show you that that representation isn’t quite right. So you iterate on it and try something different. It gives you something to respond to as opposed to just running in circles inside your own brain.

With the use of something like sticky notes or index cards you also open yourself up to interactivity. You can literally move the ideas around on your desk or on the wall, try out different combinations, different ways of structuring and organizing those ideas as you build up a map of the concepts that you’re working with, that shows which ideas are related to each other, which are different, and how they’re connected.

If you’re working large-scale enough, you can also tap into the benefit of physically navigating those ideas, moving left to right along the wall, looking at those ideas from a different perspective, which helps to tap into your spatial reasoning skills.

This particular technique of thinking with the space of ideas is one that I like to apply when when wrapping my head around a book, as you’re seeing here, both so that I can better understand the set of ideas that I just read, but perhaps more importantly, making the transition from understanding a set of ideas to putting them into action in my day-to-day life.

In the case of this particular visual book summary, it’s about creating a resource that I can look back on whenever I feel stuck in my own head and would benefit from thinking outside of my brain, using one of these techniques.

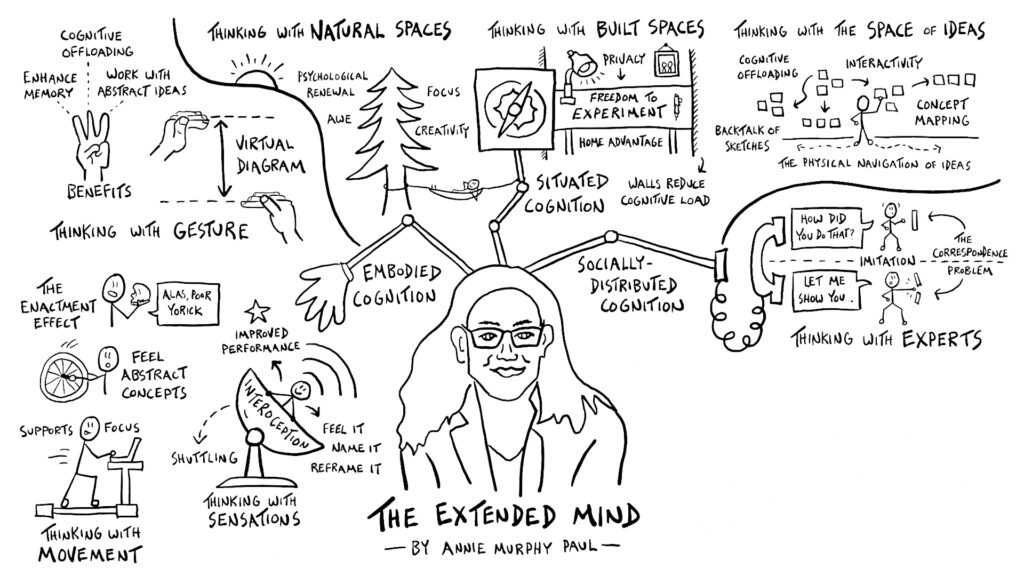

Thinking with Experts

In the final section of the book we turn to socially-distributed cognition, which is all about thinking with relationships, such as thinking with experts – tapping into the knowledge of someone who has much more experience in the current field you’re thinking about or working on, so that you can learn from that experience. An example that came to mind for me (perhaps a cliche) is the ability to break a board by punching through it in a karate class.

The way that we learn from experts is through imitation, which sometimes gets a bad rap. Paul references the cult of originality that we’re sometimes exposed to, where it’s all about coming up with your own ideas and being completely original. But in many areas of performance, imitation is often the most efficient and effective route to success, where you’re able to learn from both the successes and the failures of people who have come before you.

The thing you must watch out for, though, is the correspondence problem – the fact that there are likely differences in your particular situation compared to the one that you’re imitating. In this board-breaking analogy, maybe the material of the board that you’re trying to break is different from the example that you’re imitating.

The key to successful imitation is to spend enough time understanding why someone else’s solution is successful, and then identify how your own circumstances are different from that example, and figure out how to adapt the original solution to your situation.

Thinking with Peers

But experts aren’t the only folks that you can learn from. You peers are a great resource as well.

In the book an example was given about graduate students in the sciences, and how the development of particular skills like generating hypotheses, designing experiments, and analyzing data was more closely related to their engagement with other students in the lab and not so much the guidance they received from faculty members.

One of the things going on here is what’s called the social encoding advantage – that we actually remember social information more accurately than information taken in in a solitary environment.

Thinking with your peers is also a way to avoid confirmation bias by arguing together with the aim of arriving jointly at something close to the truth, where you fight over ideas with mutual respect, which helps you be more productive and creative in your thoughts, and also helps you to make better arguments.

Another benefit of learning within a peer group is that it leads to cascading mentorship, where the participants in that group both teach and are taught. Peer tutoring has great benefits because for the peer teacher, the simple act of teaching will change the way you think and lead to a better, deeper understanding when you’re forced to communicate a concept to someone else. For the person on the receiving end, it’s often going to be more helpful to hear what someone who is closer to your level of understanding has to say compared to the instructor, who might have too much expertise and who has forgotten what it was like to first learn that material.

Thinking with Groups

We then move from thinking with peers to the more general act of thinking with groups, where we can benefit from shared attention – when we focus on the same same objects or information at the same time as others. This is a similar idea to the social encoding advantage, where we learn better, remember better, and are more likely to act on information that has been attended to along with other people.

When working in a group you can also tap into shared motivation, where group membership itself acts as a form of intrinsic motivation, which is a nice contrast to how we commonly think about motivation as something that has to come from each person individually. It’s kind of refreshing and encouraging that that motivation can actually be shared and distributed in a group environment.

Those benefits can be amplified through behavioral synchrony – something as simple as a synchronized exercise – where coordinating your actions primes you for what Paul calls cognitive synchrony – multiple people thinking together efficiently and effectively. That behavioral synchrony helps each individual flip the switch from a focus on “I” to a focus on “we”.

When thinking in a group you can also tap into the benefit of transactive memory, where instead of one person having to remember everything, the task of knowing and remembering can be distributed among the members to create a more versatile whole, where certain people might be responsible for knowing certain things.

Paul points out here that while “group think” gets a bad rap (rightly so if it describes uncritical group thinking), it’s also worth recognizing that cognitive individualism also has its limitations and that there are plenty of ways to successfully and efficiently think within a group.

***

So what you’ve seen here are nine different ways that you can think outside of the brain, and really I’ve just scratched the surface on each of those nine. I do encourage you to pick up the book for more examples and techniques within each of those categories.

For now, though, know that you’ve got resources you can tap into when you feel like your own thinking isn’t getting you anywhere. Any one of the techniques above for getting out of your head will likely lead to some new insights.

Build Your Visual Thinking Skills

If you enjoyed the visual nature of that summary and want to develop your own visual thinking skills, then check out our library of courses:

Included with each course is access to live monthly Q & A’s to share your progress and ask questions of me and other visual thinkers from around the globe. We’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

Cheers,

-Doug