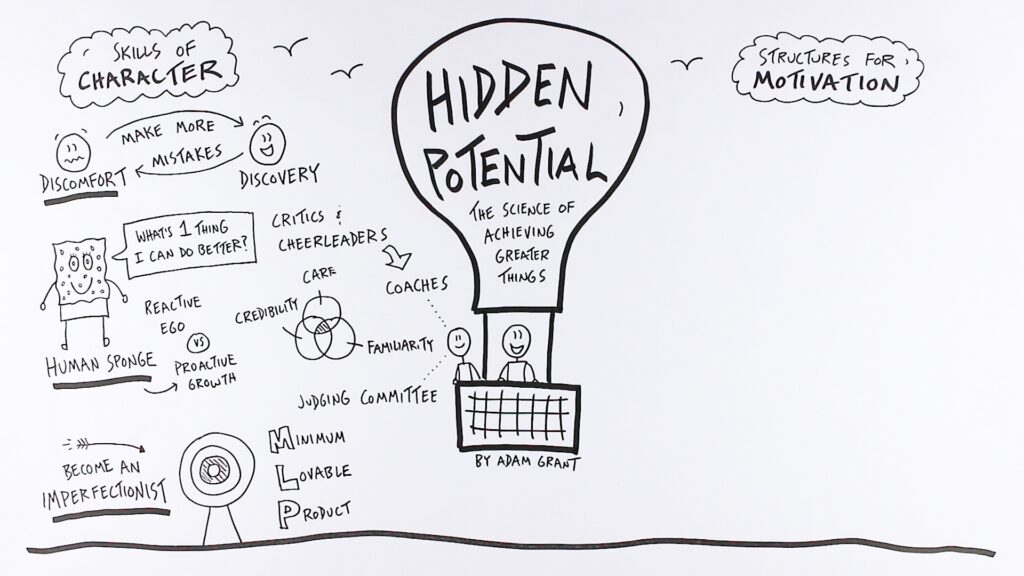

How do we improve at improving?

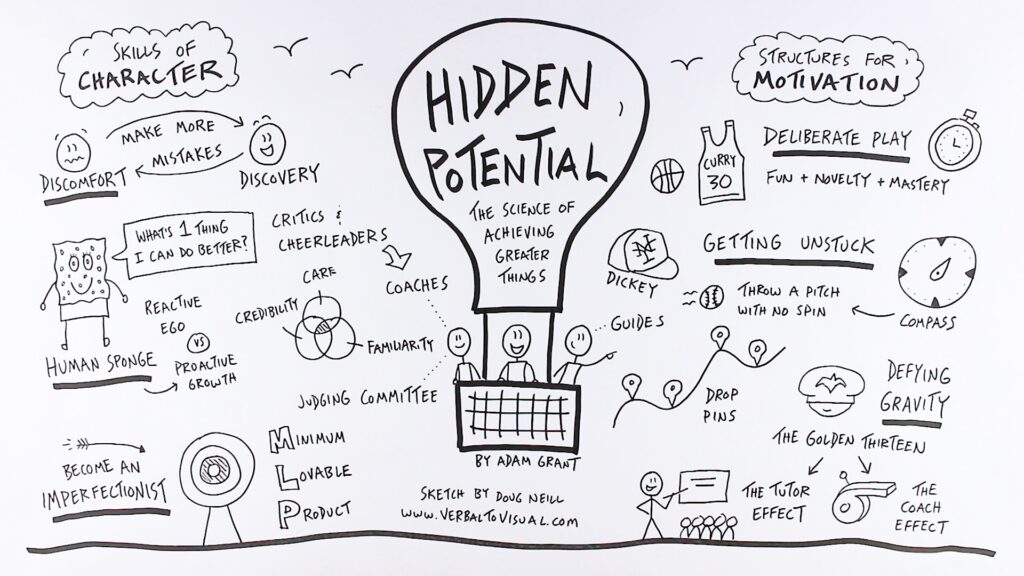

That’s the question behind Adam Grant’s book Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things. In the video above and article below I sketch out some of my favorite ideas from that book.

As Grant writes in the introduction, this book is not about ambition, it’s about aspiration. As the philosopher Agnes Callard highlights, “Ambition is the outcome you want to attain. Aspiration is the person you hope to become.”

In order to become that person and reach great heights, you need two things: You need skills of character and you need structures for motivation. Those are the first two sections of the book. I’ll mention the third toward the end of this article. But let’s start with skills of character.

Skills of Character

Grant defines character in a couple of ways that I find to be helpful. The first is that “Character is your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts.” And the second is that “If personality is how you respond on a typical day, character is how you show up on a hard day.”

Skill #1: Embrace Discomfort

Here’s the thing about hard days, though: they’re uncomfortable. Which is why one of the first things Grant suggests that you do is to not just embrace, but even seek out and at times amplify discomfort.

This is where Grant dispels the myth of learning styles, something that we’ve talked about before. As Grant writes, “The way you like to learn is what makes you most comfortable, but it isn’t necessarily how you learn best. Sometimes you even learn better in the mode that makes you the most uncomfortable, because you have to work hard at it.”

That message is reinforced by the book Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning, which shared, among other things, that effortful learning is lasting learning.

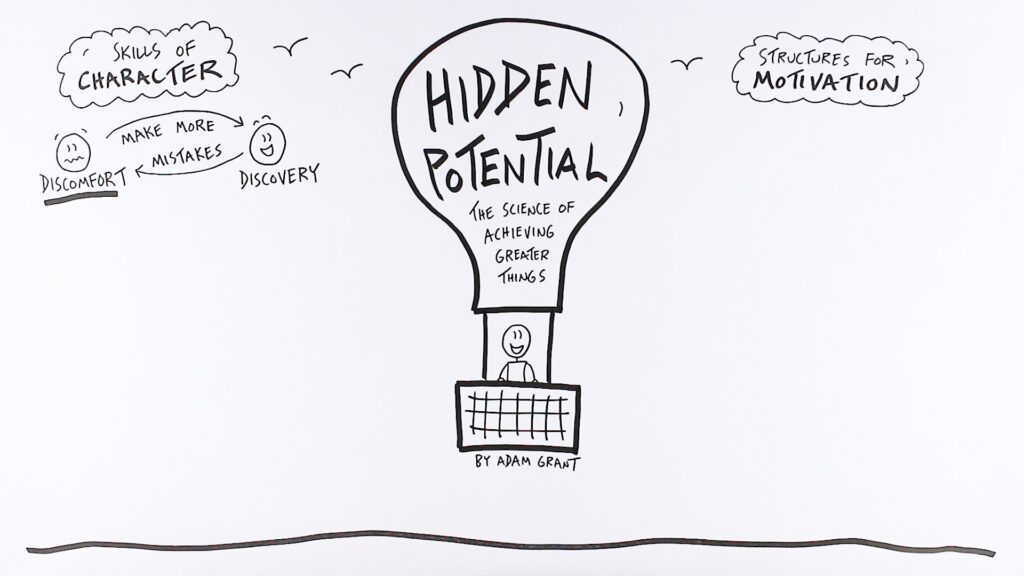

I like to think of it as a cycle moving from discomfort to discovery. It’s through the willingness to put yourself into uncomfortable situations that you learn something new—about yourself, about the world, or about the specific craft that you’re developing.

Here Grant tells two stories that I appreciate.

One is within the realm of language learning, using polyglots Benny Lewis and Sara Maria as examples. They both had rough starts with language learning, but found that the best way to learn a language is to get out and attempt to speak it. Immerse yourself in that language well before you can fully communicate in it, knowing that there’s going to be discomfort and awkwardness as you fumble your way through the various interactions throughout your day. Lewis even called it social skydiving because of how it feels to put yourself in those situations. But it’s through that discomfort and the mistakes that you make along the way that you’ll discover the ins and outs of whatever language you’re learning.

The second example is of comedian Steve Martin, who started out in standup and initially wasn’t all that good. He liked to improvise much of his set, but audiences weren’t reacting well to that. He wasn’t getting the laughs that he was hoping for. The shift towards success for him came when he started writing more, despite how uncomfortable the writing process was for him. He hated writing because of how uncomfortable it made him, but it led to better sets. So he kept doing it, and his career started taking off.

So the encouragement here is to:

- First embrace discomfort and throw your learning style out the window.

- Then seek out discomfort by being brave enough to use your knowledge as you acquire it, not waiting until you’re perfect at the thing before you do anything with it.

- And finally amplify discomfort by making more mistakes.

Skill #2: Become a Human Sponge

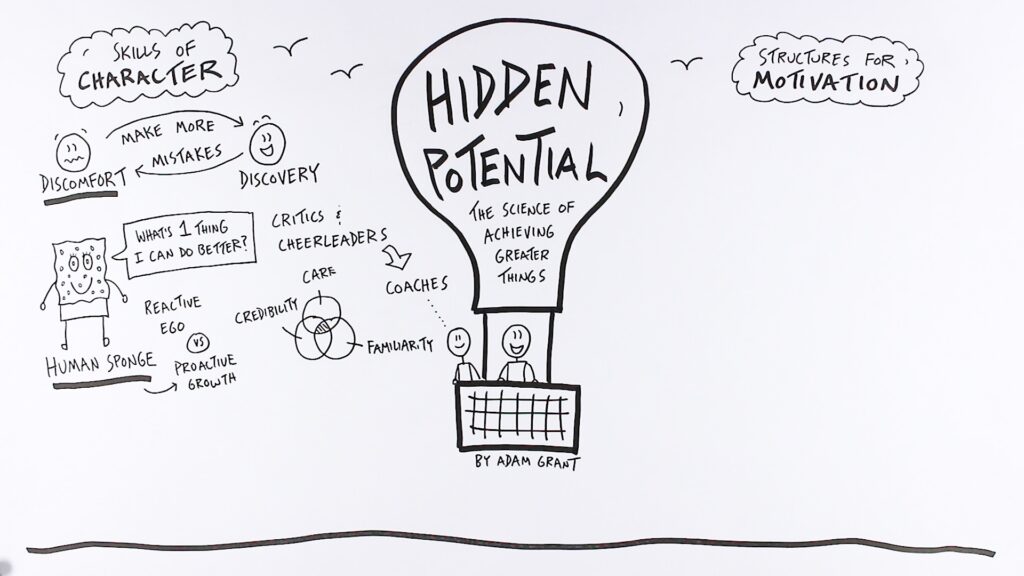

The second skill of character addresses how you can best learn from the experiences that you’re having and from the uncomfortable situations that you’re putting yourself in. Here Grant uses the sea sponge as a model, which is one of Earth’s oldest animals, great at absorbing and filtering materials and adapting to their environment. For my visual summary I’m going to use this (sea) SpongeBob SquarePants as a reminder to become a human sponge.

This has to do with how we respond to feedback, which is itself a weighty topic. I read a whole book about it called Thanks for the Feedback. You can check out my video on that book if you’re interested.

Here, though, Grant makes a distinction between responding to feedback either from the place of a reactive ego, where your identity and sense of self is challenged, versus proactive growth, where you ask the question, “What’s one thing I can do better?”

That question is powerful because it can turn both critics and cheerleaders into coaches, which you will need on your journey toward achieving greater things.

Here’s how Grant describes the difference between these three types of people. He says “It’s easy for people to be critics or cheerleaders. It’s harder to get them to be coaches. A critic sees your weaknesses and attacks your worst self. A cheerleader sees your strengths and celebrates your best self. A coach sees your potential and helps you become a better version of yourself.”

And even though you can ask this question to turn anyone into a coach, it’s still worth being discerning about who you listen to. Grant introduces a Venn diagram to help you determine which sources to trust. You want to make sure that person is someone who genuinely cares about you and your well-being, someone who has credibility within the field that you’re focusing on, and someone who’s familiar with you and your work. Those who live at the intersection make great coaches.

Skill #3: Become an Imperfectionist

In the constant pursuit of one thing better, you might fall into the trap of seeking perfection in whatever it is that you’re doing, getting to the point where you can hit the bullseye every time. Grant’s third skill of character helps you counteract that tendency, encouraging you to become an imperfectionist.

Because here are the things that perfectionists get wrong:

- They obsess over details that don’t matter

- They avoid unfamiliar situations and difficult tasks that might lead to failure (but remember how important mistakes are)

- And they berate themselves for making mistakes, which makes it harder to learn from them

So how do you get over those perfectionist tendencies that you likely have (if you’re anything like me)?

Here, Grant introduces the MLP, which is a a riff on the MVP (minimum viable produc) from the world of business. Here, though, we’re on the lookout for the Minimum Lovable Product. To be lovable, it doesn’t have to be perfect. So instead of shooting for ten out of ten, instead of going for that bullseye, shoot for an 8 or 9. Be okay with some imperfection.

As Grant writes, “Tolerating flaws isn’t just something novices do. It’s part of becoming an expert and continuing to gain mastery. The more you grow, the better you know which flaws are acceptable.”

One way that you can get better at determining which flaws are acceptable is by establishing a judging committee that can give you feedback on your work. That’s what Grant does with his books. He shares a draft with friends who can act as coaches because they fall at the intersection of the Venn diagram that I mentioned above. He asks them to give his work a score from 0 to 10. If he gets all eights and nines and maybe even some tens, he knows he’s good to go. If he gets lower than that, he can ask the question, “What’s the one thing that I can do better to move towards minimum lovable?” To move from a 5, 6, or 7 up to an 8 or 9?

Over time, the more you go through that process, the more examples you have of what needs to be improved, the clearer it will become which of those flaws are okay as they are, which things don’t need to be improved.

Structures for Motivation

Let’s now talk about motivation. As Grant writes, “Character skills aren’t always enough to travel great distances. Many new skills don’t come with a manual, and steeper hills often require a lift. That life comes in the form of scaffolding: a temporary support structure that enables us to scale heights we couldn’t reach on our own. It helps us build the resilience to overcome obstacles that threaten to overwhelm us and limit our growth.”

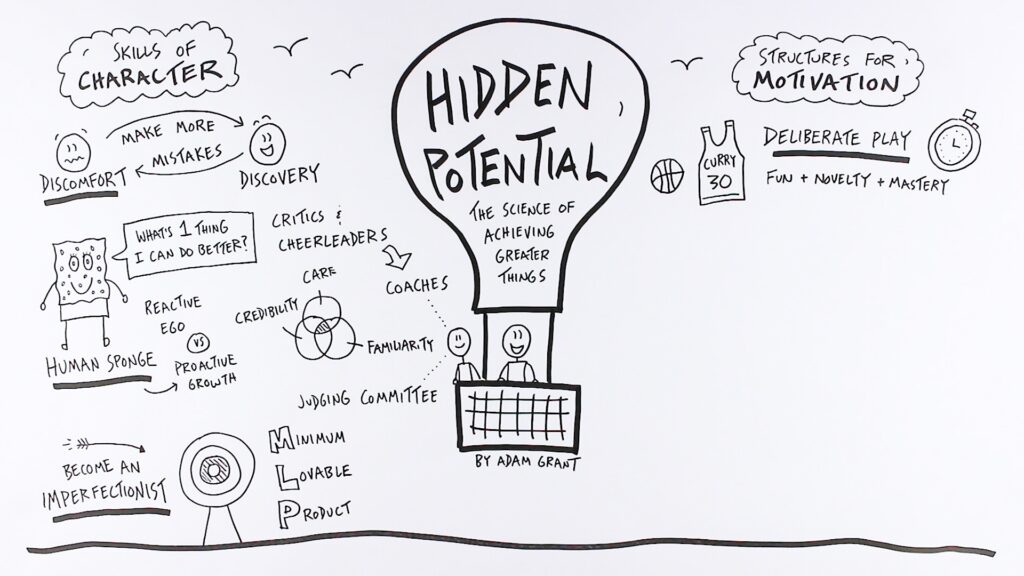

Structure #1: Deliberate Play

The first structure for motivation is demonstrated by my dad’s favorite basketball player, Steph Curry, who has gotten a lot of attention for his workouts. Curry’s trainer, Brandon Payne, developed a variety of never-boring workouts where there is always a time or a number to beat so that you’re always competing with your past self, but at the same time, it’s still just a game that you get to have fun with.

This is called deliberate play, and it’s about making skill development enjoyable by blending fun with novelty and mastery. It’s different from deliberate practice, which could lead to burnout or boreout (a term that Grant coined to describe the emotional deadening that occurs when you’re under stimulated, which can happen with certain rote practice activities).

Novelty and variety is key here, both for keeping it fun and interesting and also because it’s helpful for learning. That’s another thing that we learned from the book Make It Stick: regularly switching up the conditions that you’re working in or the tasks that you’re working on is more helpful than focusing on one tiny skill in isolation, because that’s rarely how you actually use the skill in real life.

Musicians are another good example of deliberate play. As Grant writes, “Elite musicians are rarely driven by obsessive compulsion. They’re usually fueled by what psychologists call harmonious passion. Harmonious passion is taking joy in a process rather than feeling pressured to achieve an outcome. You’re no longer practicing under the specter of ‘I should be studying. I’m supposed to practice.’ You’re drawn into a web of want. ‘I feel like studying. I’m excited to practice.’ That makes it easier to find flow. You slip quickly into the zone of total absorption, where the world melts away and you become one with your instrument. Instead of controlling your life, practicing enriches your life.”

So the idea here is to seek out or develop a menu of deliberate play activities. That menu could come from a teacher or a coach, or you could just develop it yourself.

Note that play is important, but so too is taking breaks, which reduce fatigue, raise your energy, unlock fresh ideas, and even deepen your learning. That’s what spaced repetition is all about (again, go check out Make It Stick!). For more on the back-and-forth between energy expenditure in the form of deliberate play and energy recovery, go check out The Power of Full Engagement, which is all about managing your energy as opposed to just managing your time.

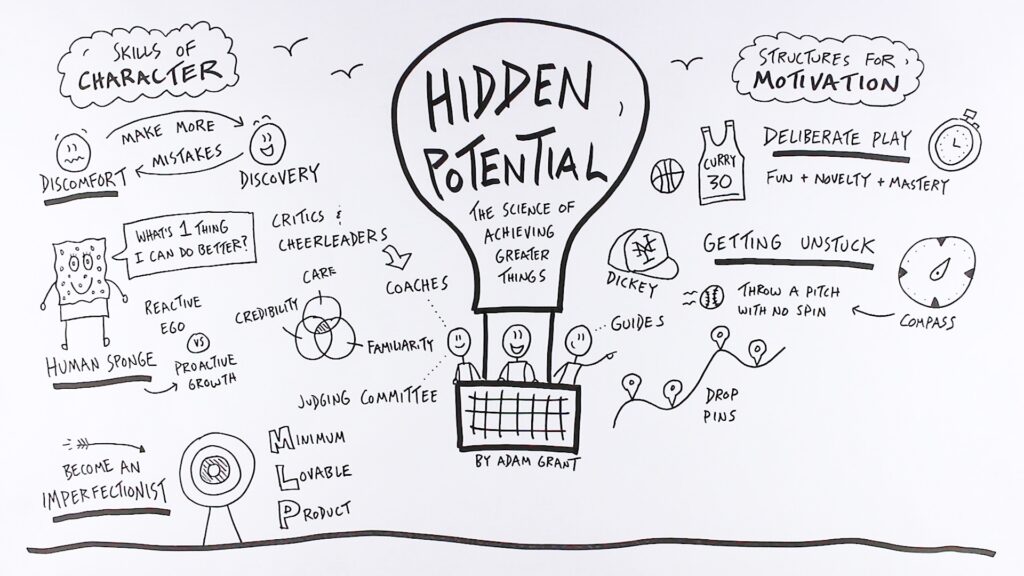

Structure #2: Getting Unstuck

With the second structure for motivation we’ve got another sports example, this one from the world of baseball with pitcher R.A. Dickey, who spent years toiling away in the minor leagues, feeling stuck, languishing in relative mediocrity and seeing little-to-no progress.

In order to get unstuck, he needed a couple of scaffolds. In this case, two navigational tools.

The first was a compass. He needed a direction in which to focus his efforts. He decided on the most challenging pitch in all of baseball, the knuckleball, which is where you throw a pitch with no spin, which then has unpredictable behavior that makes it difficult to hit.

The second navigational tool needed is some guides, in this case experienced knuckleballers that could point him in the right direction. A key role of a guide is to drop pins: identify the key landmarks and turning points on this particular journey. They can show you what to expect and give you some tips. But importantly, not every single piece of advice will necessarily work for you.

In order for Dickey to learn how to throw a knuckleball, he first had to do a lot of unlearning of the basic mechanics that he’d been practicing since a child and then learn the new mechanics that are needed to throw a good knuckleball. From his guides he learned about good arm placement, keeping his hips forward, and streamlining his windup. But he also found out that he needed to ignore their advice of throwing slower. That didn’t work for him.

So the key here is not to rely on any single guide and also give yourself permission to ignore the tips that don’t work for you.

By following his compass and learning what he could from the guides that he brought into his life, Dickey was able to make it back to the majors and win the Cy Young Award, which is granted to the best pitcher in the league. As Grant writes, “It took seven trips down to the minors and seven years of knuckleball effort to become an overnight success. What looks like a big breakthrough is usually the accumulation of small wins.”

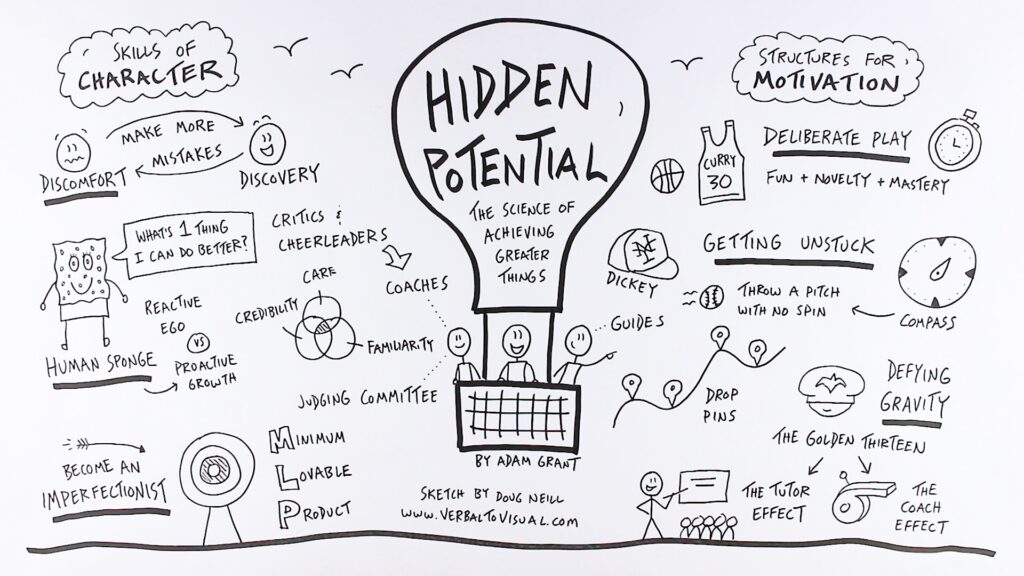

Structure #3: Defying Gravity

With the third and final structure for motivation, we’re going to talk about defying gravity. No, this is not about Wicked (though in theme it is). Instead, Grant tells the story of The Golden Thirteen, the first Black men to enter officer training in the US Navy back in 1944.

As Grant writes, “That branch of the military was known to be particularly prejudiced, banning Black citizens from enlisting altogether just a quarter century prior.” So you can imagine the challenges and obstacles they faced throughout that officer training experience.

To help each other through that experience, they provided scaffolding for each other in two key ways.

First, they divvied up the topics in their textbooks, and each member would teach their specific expertise to the rest of the group. This employs the principle that the best way to learn is to teach, what psychologists call the tutor effect, which makes use of the fact that you will remember things better by recalling them from memory, and you understand it better when you have to explain it to others, when you get outside of your own head and share it in a way that others will understand it.

In addition to playing the role of teacher to each other, they also played the role of coach, which Grant dubbed the coach effect. He writes, “Teaching others can build our competence, but it’s coaching others that elevates our confidence. The coach effect captures how we can marshal motivation by offering the encouragement to others that we need for ourselves.”

So by both teaching each other and encouraging each other, all of those men passed the officer’s exam with flying colors, earning the highest marks in Navy history.

Here’s how Grant sums up the takeaways from this story: “At times like this, we’re advised to pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps. The message is that we need to look inside ourselves for hidden reserves of confidence and know-how, but it’s actually in turning outward to harness resources with and for others that we discover and develop our hidden potential. When the odds are against us, focusing beyond ourselves is what launches us off the ground.”

Section Three: Systems of Opportunity

In the third section of the book, Grant shifts from a focus on achieving greater things yourself to creating systems of opportunity for others, with a focus on education (how to design schools that bring the best out of all your students), work within teams (how to unearth collective intelligence among groups) and the interview and college admissions process (how to restructure those to actually find the people who have the most potential, not just those who look good on paper).

To explore those topics, I encourage you to pick up the book yourself. I hope that what I’ve shared here has shown you that this is a book worth digging into.

Closing Reflections

I also encourage you to look for an opportunity to incorporate one or two of these principles into your life as you pursue great things.

How might you embrace, seek out, and even amplify discomfort?

To whom can you ask the question, “What’s one thing I can do better?” as you embrace proactive growth and become a human sponge?

How might you become an imperfectionist? What does a minimum lovable product look like in your work? And how can you embrace the imperfection that comes with that pursuit?

What deliberate play activities can you start incorporating into your life?

What’s your compass, and who are the guides that can help you get unstuck?

Who’s part of your community that’s with you in the trenches where you can support each other through the tutor effect and the coach effect?

If you think that your pursuits would benefit from some visual processing skills, do come join us inside of Verbal to Visual, where you’ll see a lot of those principles in action.

Cheers,

-Doug