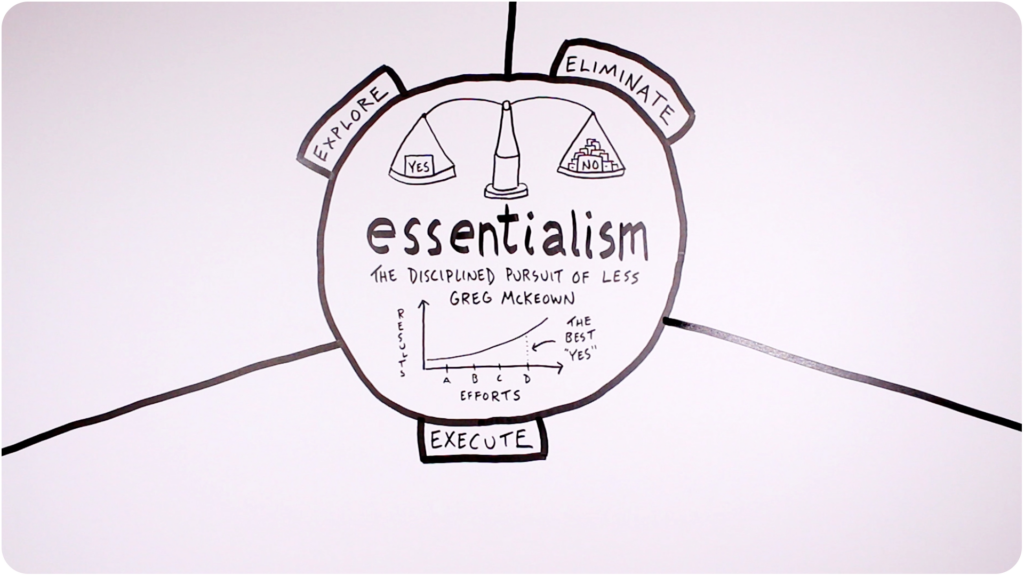

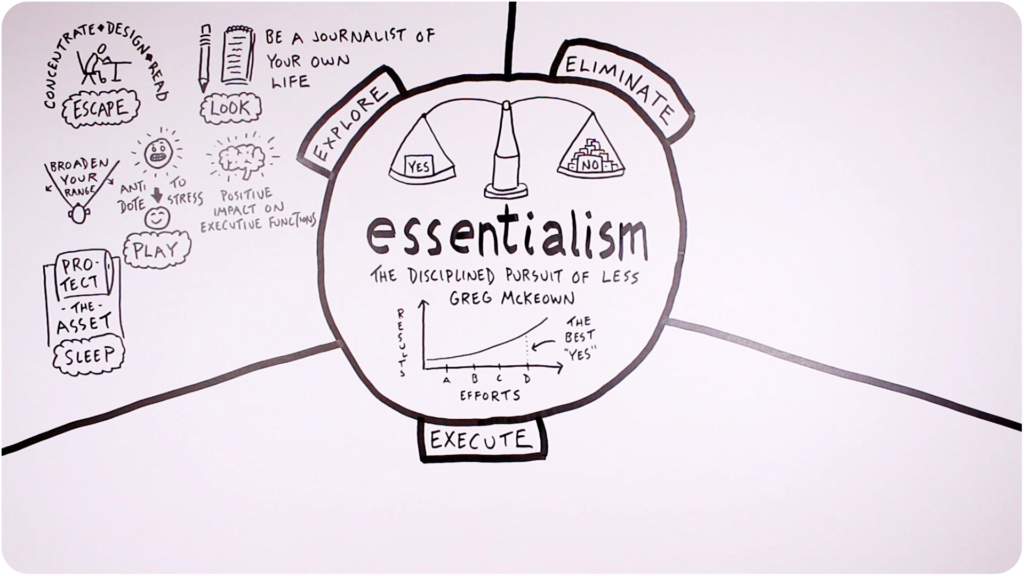

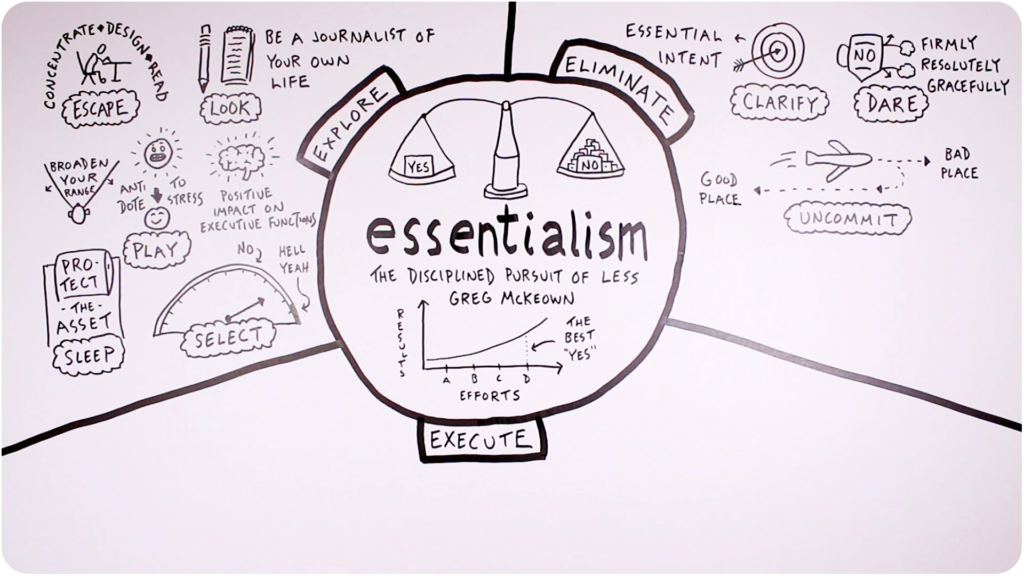

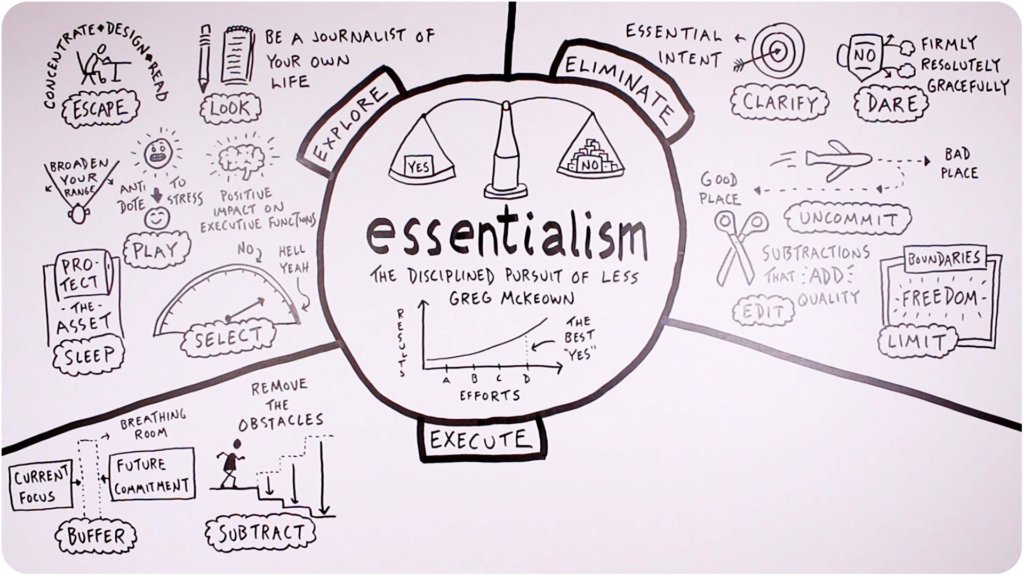

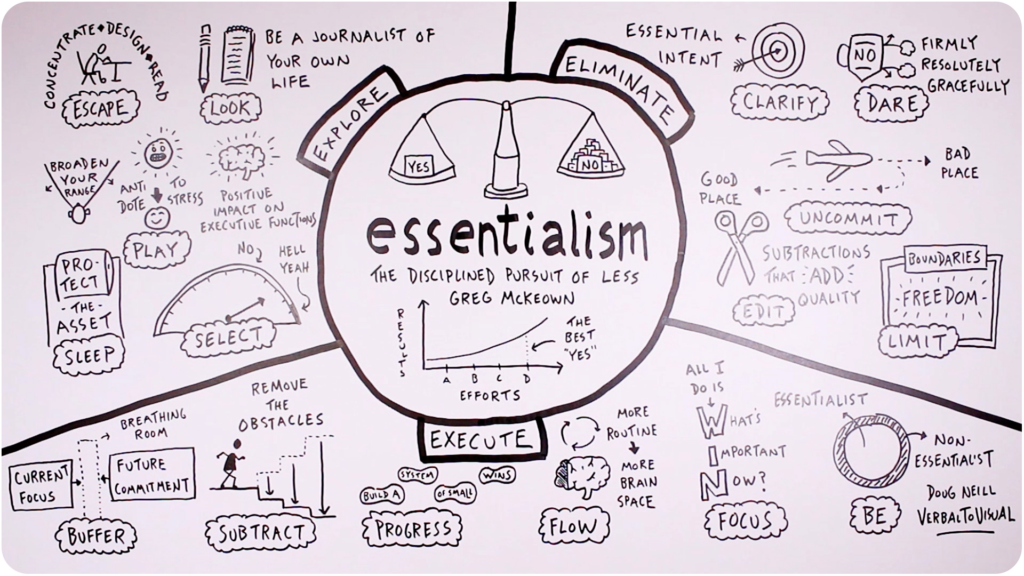

Today I’d like to share a visual summary of the book Essentialism by Greg McKeown.

In an era that emphasizes having more, doing more, and achieving more, this book’s tagline of the disciplined pursuit of less is intriguing.

Approaching my life and my work with an essentialist mindset appeals to me, especially in the current stage of my creative career as I look toward what future projects I might want to take on.

I hope that you find these ideas useful and actionable. To dig deeper into them, do go pick up the book. It’s a great read.

The Core of Essentialism

Let’s start with two ideas that are at the core of essentialism.

The first is that for every single thing that you say “yes” to, that means you’re going to have to say “no” to a bunch of other things.

For that reason it’s worth putting a lot of value in your yes, and also not being afraid to say no.

But how do you determine what to say yes to?

As you work to answer that question (with the help of the ideas that follow), keep in mind is that not all effort is created equal. Certain types of effort yield more results that others. What you’re on the lookout for are the best places to put your effort, the best “yes”–the tasks and the projects that you can take on that will yield the greatest results.

With those core ideas and core questions in mind, we jump into the three sections of this book: explore, eliminate, and execute.

Explore

Each chapter of this book has a single-word title, always a verb. I appreciate that about this book–the simplicity and the action-oriented nature of it.

Escape

Within the explore section of the book, you must escape. You’ve got to create a time and a space where you can concentrate, where you can design, and where you can read.

This is all about intentionally creating times when you are unavailable in order to give yourself the space to do deep thinking and deep work.

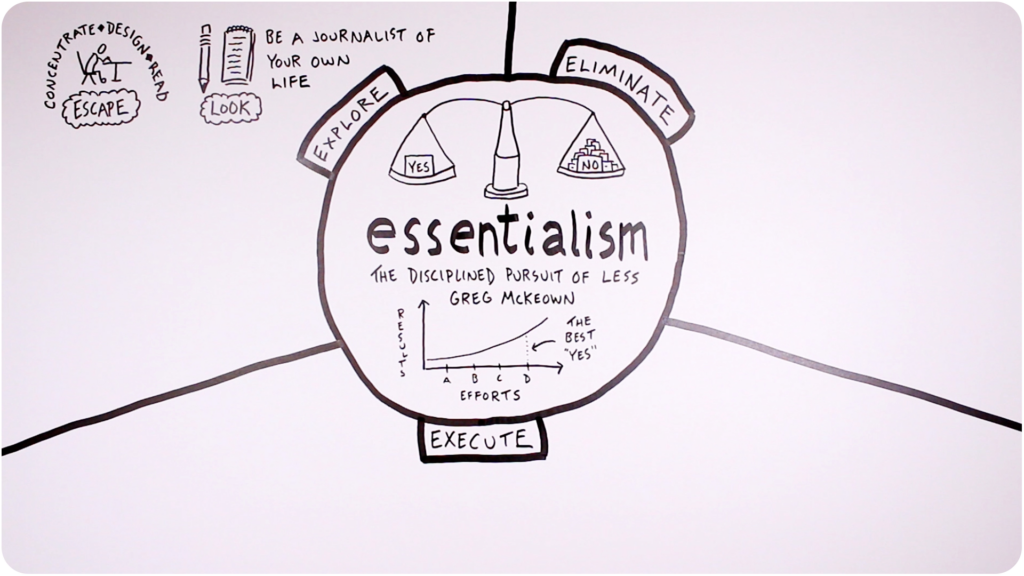

Look

You’ve also go to look. You’ve got to hone your observational skills and be a journalist of your own life.

The idea from this chapter that I found to be the most helpful relates to the morning journaling that I do, specifically the prompt to “look for the lead.” As I look back on the past day or the past week, I ask myself what the lead might be to the story of thank chunk of time.

That’s what I start with, and then I keep writing.

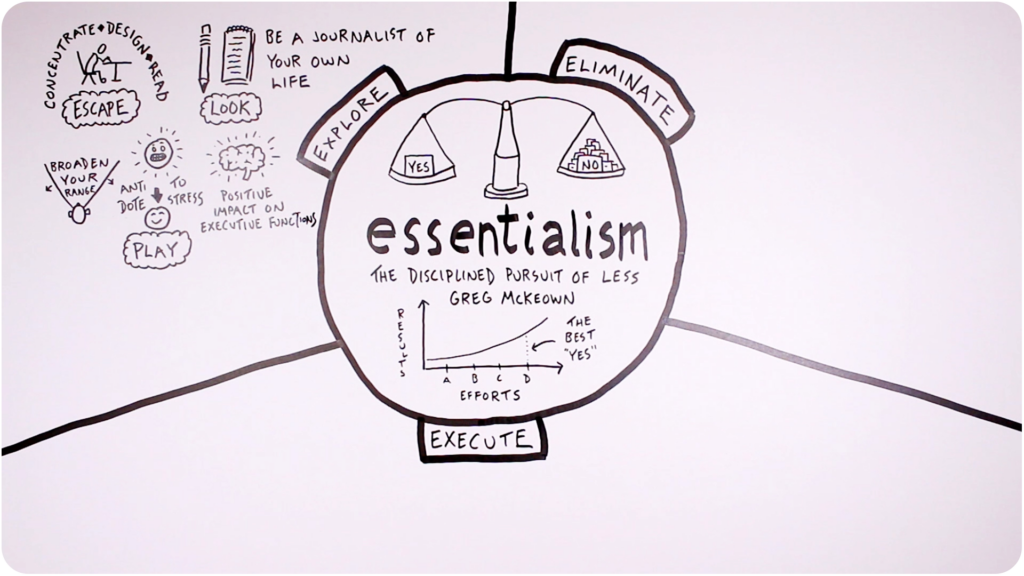

Play

You also must play. The value of playing lies in its ability to broaden the range of options available to you. There’s an expansion of awareness that happens when you enter a state of play, and that expansion helps you to see things that you didn’t notice before and consider options that previously you’d been blind to.

Play is also a very clear antidote to stress, which is a regular component in all of our lives, to varying degrees.

Finally, play has a positive impact on executive functions like planning, deciding, anticipating, and prioritizing. Regular play helps the brain to do those things better.

Sleep

Sleep is an important activity as well. It’s how you protect the asset: your brain and body; your ability to make good decisions. Without enough sleep you lose the ability to see what actually is essential, and the quality of your effort and attention steadily declines.

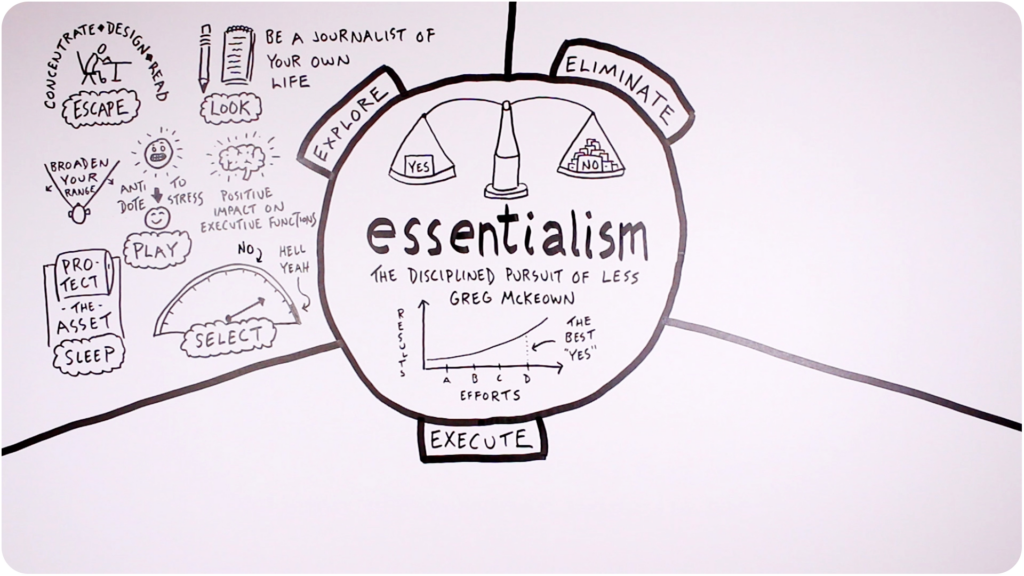

Select

In order to put your efforts toward the things that are most important, you have to select. You can’t say yes to everything, and you have to decide some metric by which to determine what gets it and what doesn’t.

Here McKeown brings in the idea from Derek Sivers of “Hell yeah!” or “No.” There’s no in between. And that “hell yeah” only gets a very small percentage, so if you don’t have that immediate reaction, it’s probably not worth doing.

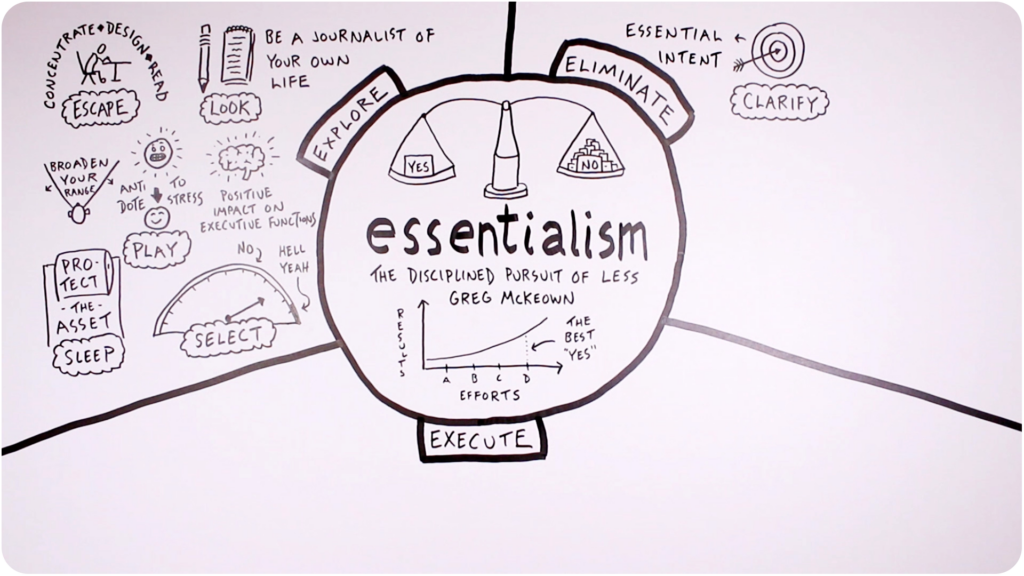

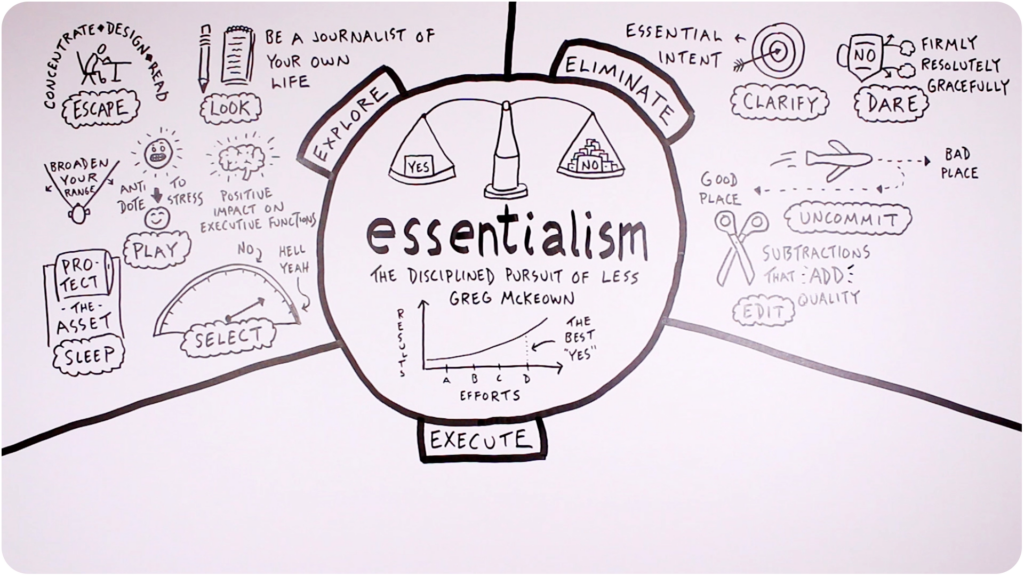

Eliminate

From that exploratory section of the book, we move on to eliminating.

Clarify

To eliminate, you must first clarify. You’ve got to decide what the target is that you’re shooting for.

At the center of that target is your essential intent–a guiding principle that is both measurable and inspiration. Without having your essential intent defined, it makes it a whole lot harder to know what things to say yes to and which things to say no to.

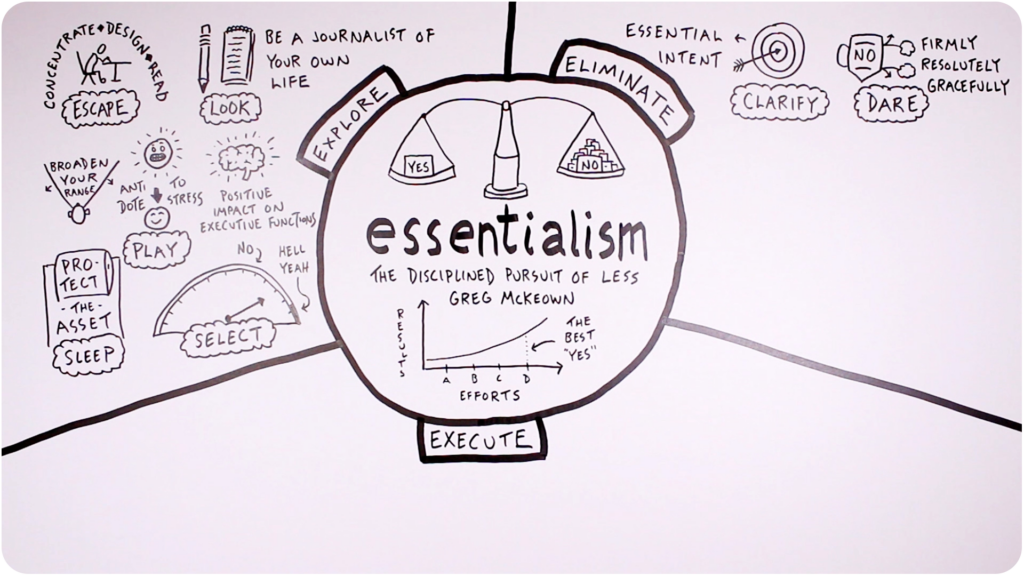

Dare

Of those two responses – yes and no – it’s understandable that it’s often harder to say no than it is to say yes. But saying no is something that you must dare to do.

You must dare to say no even if it makes you unpopular, because as McKeown puts it, saying no often means trading popularity for respect. In order to make that trade, however, you do need to say no firmly, resolutely, and gracefully.

That’s a hard thing to do. It will take effort and practice to say no well, but that effort will be worth it.

Uncommit

Ideally you’ll get good at saying no up front, but sometimes you might need to uncommit.

If you recognize that the direction you’re going is taking you toward a place you don’t want to go, you’ve got to make the tough decision of turning the plane around and start moving toward a better place, even if that turn requires a decent amount of energy.

Edit

You’ve also got to edit along the way as you look for those subtractions that actually add quality to your life and to your work.

This is the “kill your darlings” of Stephen King, the “if I had more time this would be a lot shorter.”

This is where you move from that journalism mindset when you were exploring to an editor’s mindset, looking for opportunities to cut out anything that isn’t essential so that there’s more space and attention given to what is.

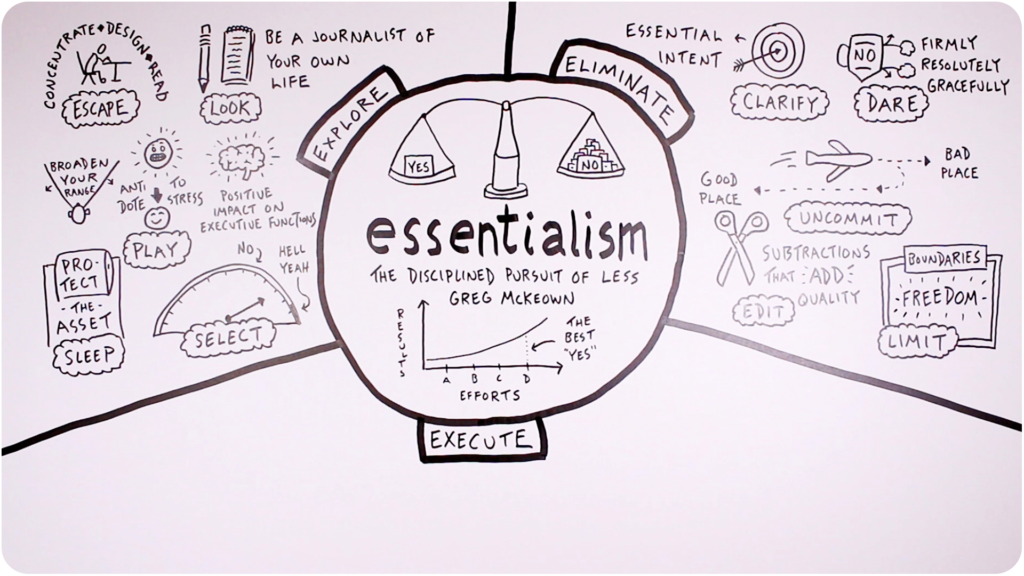

Limit

Where editing is something that often occurs after-the-fact, you also have the opportunity to limit your options up front.

Create boundaries in your life and in your work within which you can actually feel a sense of freedom, a safe space that you’ve created where you can do your thing uninterrupted.

I think this applies both to the limits that you put on yourself for any particular creative task as well as the boundaries that you set up with other people. Appropriate boundaries within your relationships are what creates that sense of freedom.

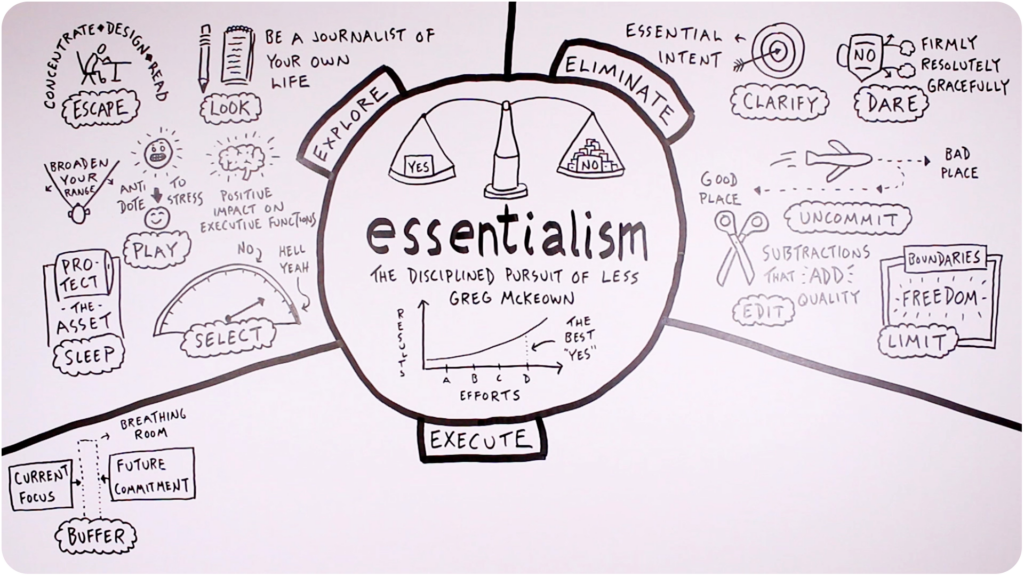

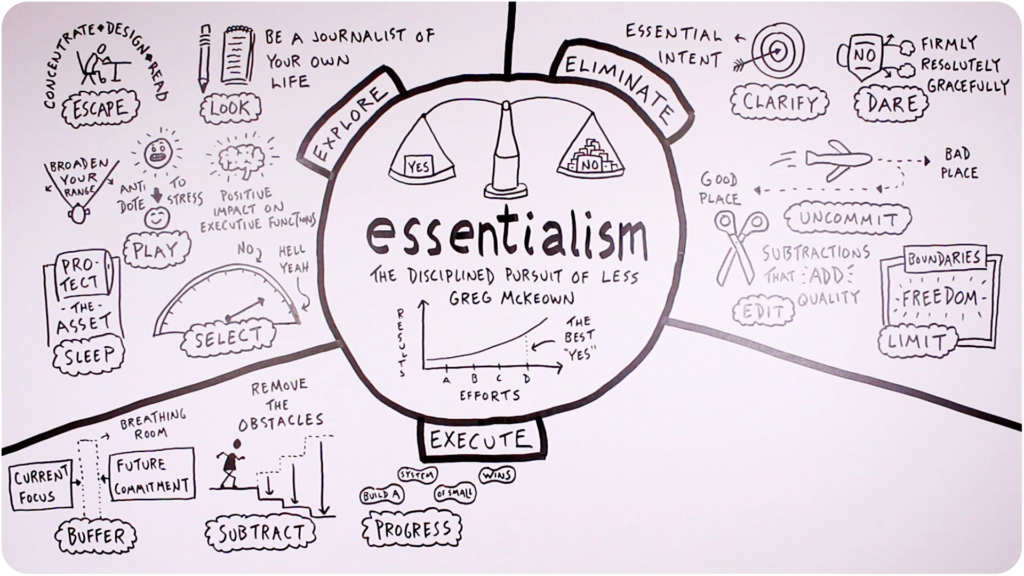

Execute

From there we move on to the act of executing on the things that you’ve chosen to say yes to.

Buffer

We start with the value of creating a buffer. Create some space in between whatever your current focus is and whatever future commitment is coming your way.

That bit of breathing room will allow you to execute on your ideas more effectively, with the goal that your efforts fall more within that “D” range (high results) compared to the “A” range (low results).

Without the appropriate time buffers and financial buffers, there’s the risk that the quality of your effort will decline. Because your attention (either consciously or subconsciously) is elsewhere, worrying about the rapidly approaching upcoming commitment.

Subtract

In order to execute on an idea effectively, you also must subtract. You’ve got to take a close look at the steps underlying your creative process and remove the obstacles that make those steps more difficult. Instead of feeling like you’re trudging up a stairway, maybe it can feel more like walking down one.

For example, when I create videos like the one at the top of this post, I sometimes see the task of putting my face on camera for an intro and outro as an obstacle that’s actually keeping me from doing more and better work. That’s why I’ve been experimenting with subtracting that from my process, because it might not be essential for my task here of sharing interesting ideas and helping others develop useful skills.

So think about what the obstacles are in your process that you might be able to remove.

Progress

The emphasis here is on progress, not huge leaps of it but instead small wins. Create a system of small wins for yourself, steps that you can take each day that allow you to start small and build momentum over time.

Do you have a system like that in place? Is that system rooted in small steps?

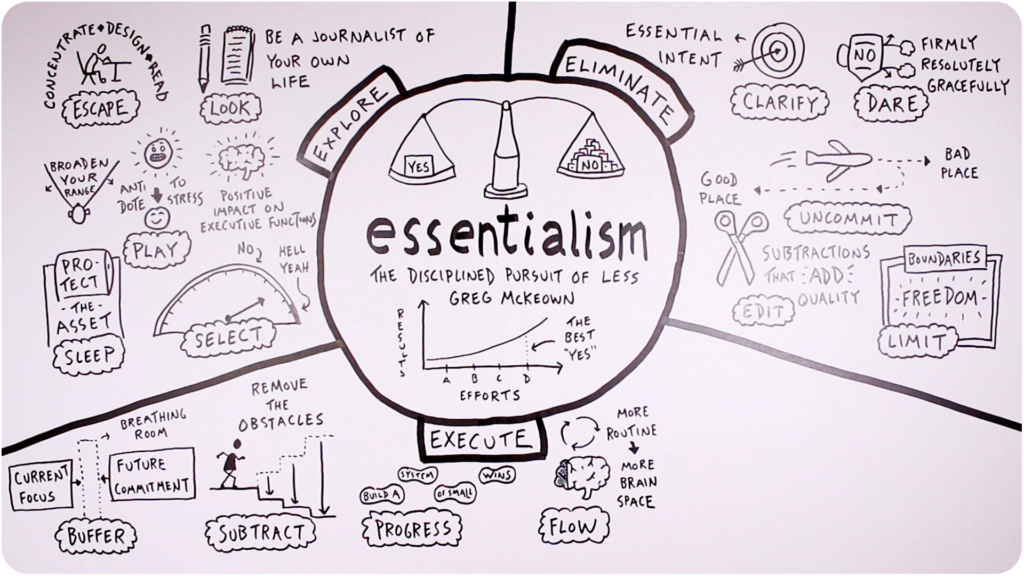

Flow

As you build that system, look for the things that get you in a state of flow. Look for consistent routines that you can put in place for yourself, because the more routine something becomes, the more that opens up the rest of your brain to devote to the challenging task in front of you.

That’s another piece that can increase the quality of your effort, and thereby the likelihood that your effort will yield the best results.

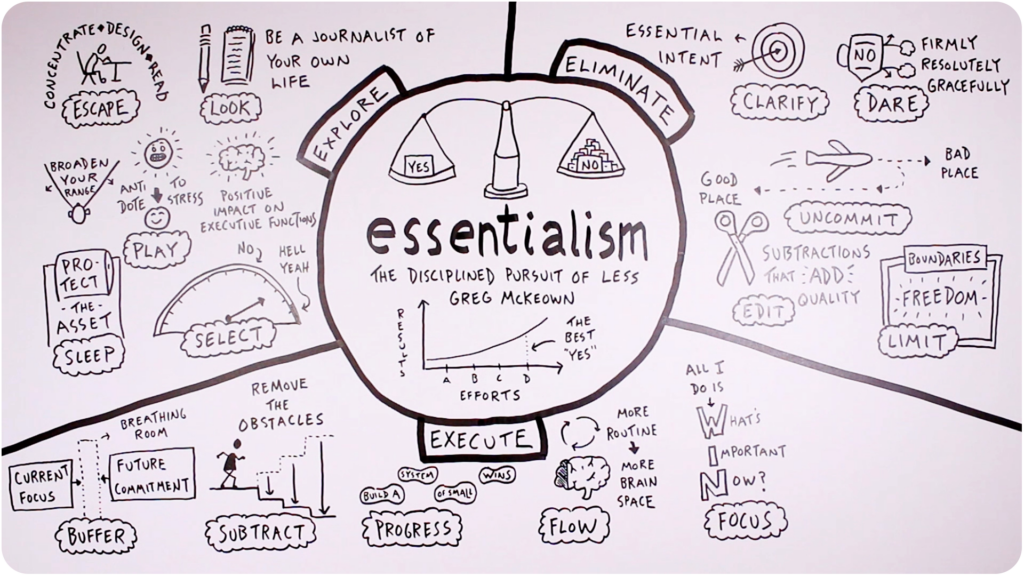

Focus

As you on the progress of small wins and seek out that state of flow, what will help is a regular state of focus.

Focus your attention and energy on WINning–asking the question “What’s Important Now?”

Don’t dwell on something that happened in the past or stress about something that might happen in the future, but give quality attention to the present, and choose to act on the thing that is most important right now.

Be

To wrap things ups, McKeown looks at what it means to actually BE an essentialist, because essentialism isn’t something that you do, it’s something that you are.

He encourages us to move the essentialist part to the core, to live from a sense of essentialism and push the non-essentialist to the exterior, making that a smaller and smaller part of who you are.

As you’ve seen here, one of the tools that I use to help me decide what is essential and then execute well on the things that I’ve chosen to say yes to is visual note-taking, which involves creating diagrams and small sketches to help you wrap your head around whatever’s in front of you.

If you would like to develop that skill yourself and make your yeses a little bit more impactful, then check out the resources inside of Verbal to Visual.

There you’re find a set of complete-at-your-own-pace online courses, plus weekly live workshops and global community of visual thinkers who are applying their skills to work that they care about.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this visual summary of Essentialism, and I look forward to sharing more ideas with you next time.

Until then,

-Doug