In his book Digital Minimalism, Cal Newport makes the case for being more intentional about the technologies that you allow into your life.

In the video above and post below I sketch out some of my favorite ideas from that book and then share how I’m applying them both in my personal and professional life.

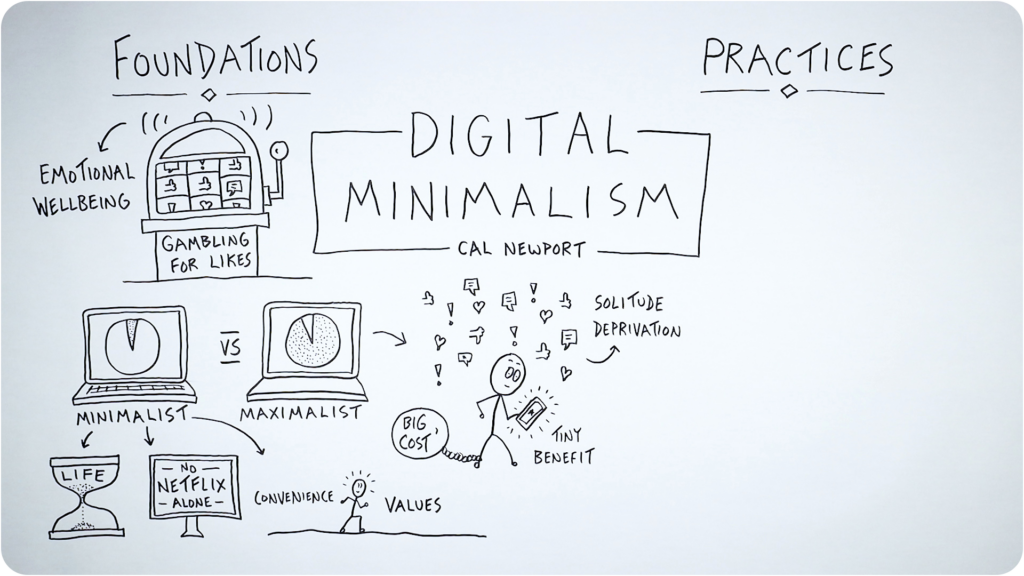

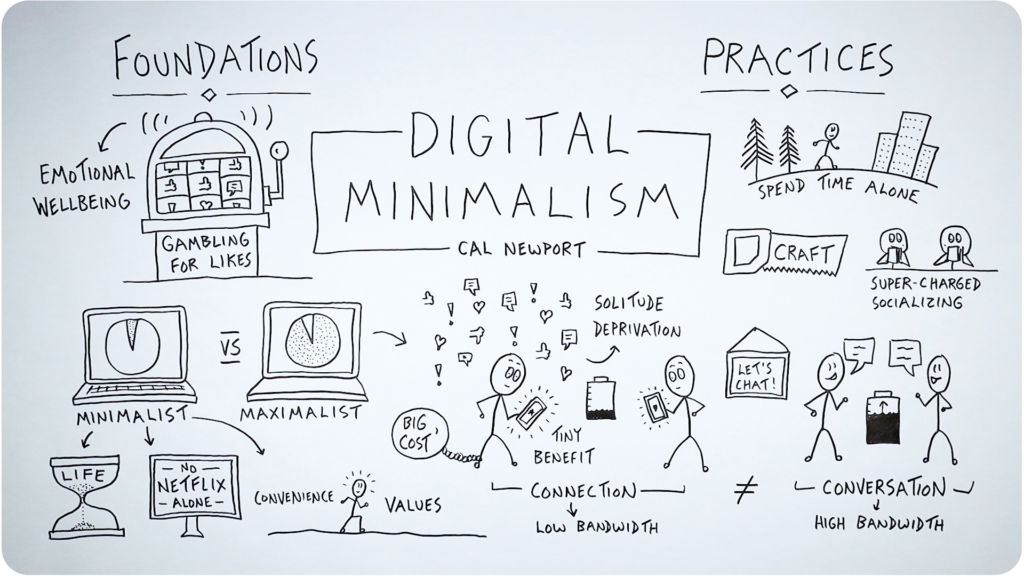

The book is broken down into two sections: first Foundations and then Practices.

The Foundations of Digital Minimalism

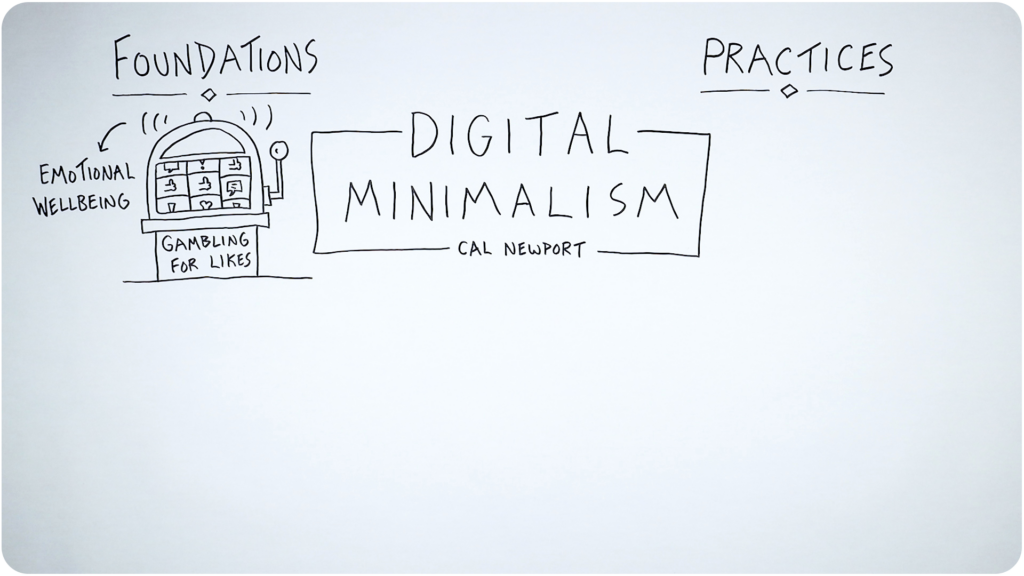

On the foundational side, Newport shows us how technology is not neutral. In particular, the software that we use has been carefully engineered to create behavioral addictions that lead to more eyeballs on the screen and more money in the pockets of big tech companies.

Every time you whip out your phone and refresh your social media app of choice, you’re gambling for likes. Each time you see new likes or comments, you get a dopamine hit. When you don’t see that, it’s easy to feel that no one cares and that your life isn’t interesting enough. That’s a pretty dangerous game that to be playing with your overall emotional well-being.

No matter how many likes we get or how many positive comments we see, those positive feelings never reach a feeling of sustained satisfaction. The feeling is always fleeting, disappearing within minutes, causing us to check it again, hoping that new likes have rolled in. This relationship to technology is not healthy, which is what prompted Newport to explore how to combat it.

What he came up with was Digital Minimalism, which he describes as:

“a philosophy of technology use in which you focus your online time on a small number of carefully selected and optimized activities that strongly support things you value, and then happily miss out on everything else.”

Cal Newport, defining Digital Minimalism

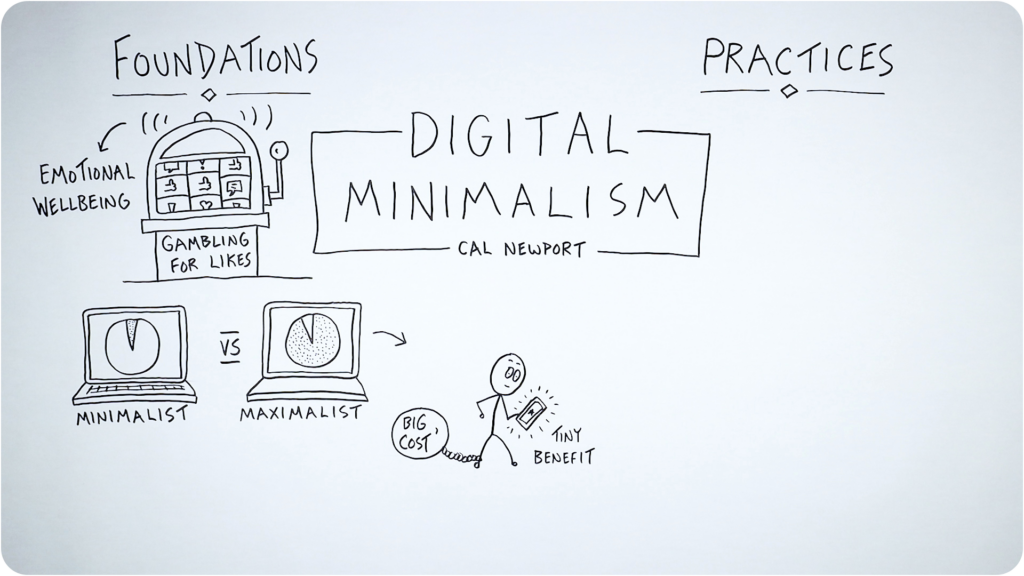

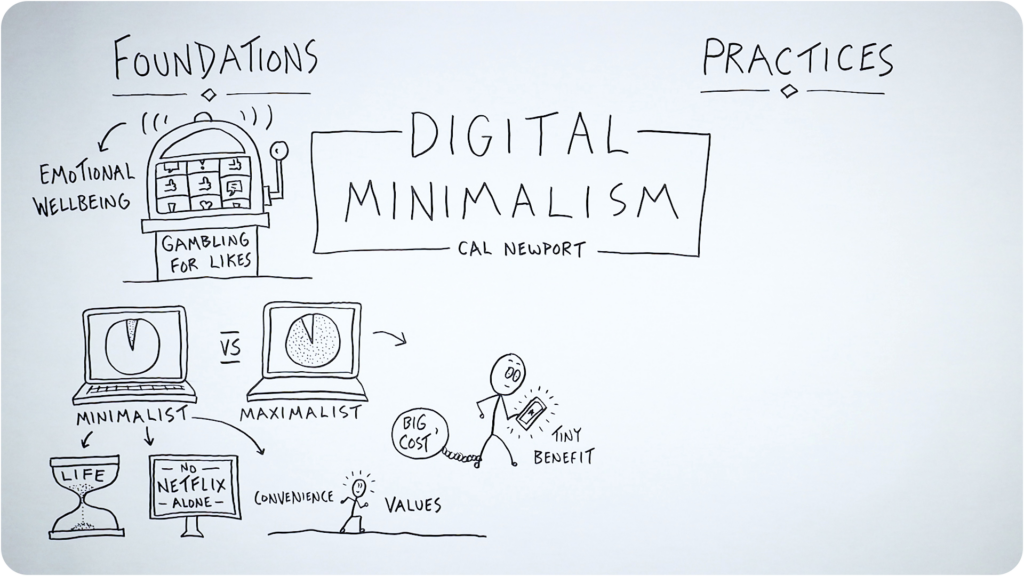

He contrasts the minimalist approach to a maximalist approach. As a maximalist, the approach is to adopt any new technology so long as it provides even a tiny benefit to your life. The problem with that, as Newport points out, is that if we only look at the benefits we might be neglecting the significant cost that comes along with the adoption of any particular technology.

Instead of the approach that any potential benefit is worth it, Newport proposes the minimalist approach, where you recognize three things.

First: life is short.

You only have so much time and attention, and therefore any amount of clutter in your life is very costly. Here he quotes Thoreau, who said:

“The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.”

Henry David Thoreau

How much life are you giving up in order to reap the particular benefit of any given technology?

Second: optimization is important.

It’s not just if you’ll use a particular technology, but also how you’ll use it. Take Netflix for example. It’s not just a matter of whether you watch Netflix or you don’t. Instead, if you choose to bring Netflix into your life, you might add the optimization of not ever watching Netflix alone. You still get to enjoy your favorite shows, but only with other people. That keeps if from becoming a technology that creeps in to take up more and more of your time.

Third: intentionality is satisfying.

It feels good to move in the direction of your values, as opposed to always just falling back on convenience.

To get a taste for the life of a digital minimalist, Newport encourages you to take on a digital declutter: a 30-day break from optional technologies. Before you do that, though, it’s important to plan out replacements. Decide what you will do instead of scrolling Instagram for 45 minutes every day or instead of watching Netflix for two hours every night.

That’s where the practices come.

The Practices of Digital Minimalism

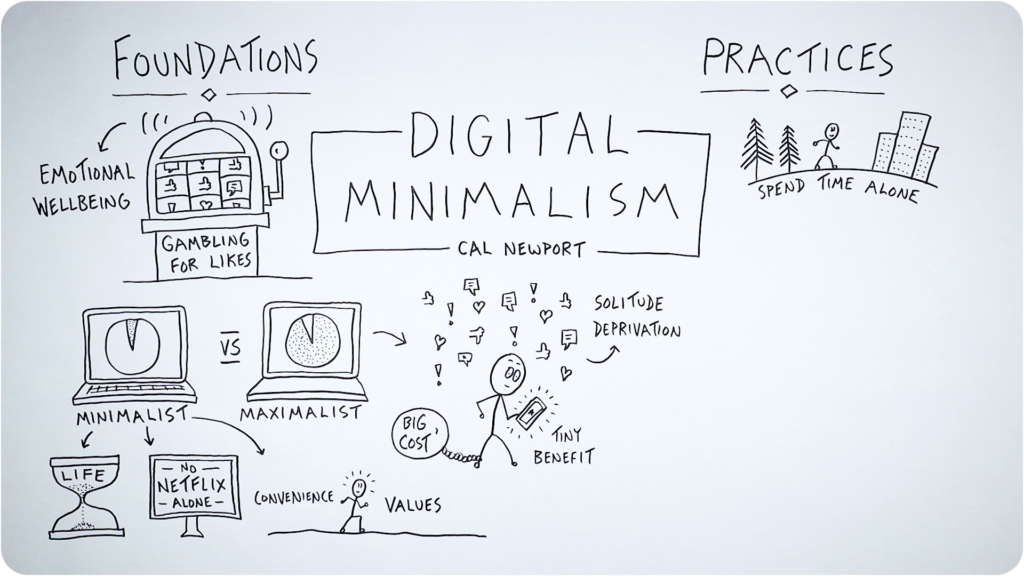

The first practice that Newport describes is in response to one particular effect of heavy social media use: solitude deprivation.

Because of all of the ways that we can connect with other people on our phone (a device that you always have with you), that creates the condition where it’s possible to completely banish solitude from your life. That deprivation of solitude has contributed to the sharp rise in anxiety and depression that we’ve seen in recent years.

The countermeasure to that solitude deprivation is pretty straightforward: spend time alone.

Newport encourages you to take long walks. Not with your phone out, not with your headphones on listening to a new podcast, but simply being with your own thoughts. He defines solitude as the state where your mind is free from input of other minds, which is quite refreshing these days.

You can use that time to think through a professional problem, do some self-reflection on a particular aspect of your life, or take what Newport calls gratitude walks – just enjoying nice weather and whatever scenery surrounds you. Paradoxically, that solitude will likely make you appreciate human connection when you get back to it.

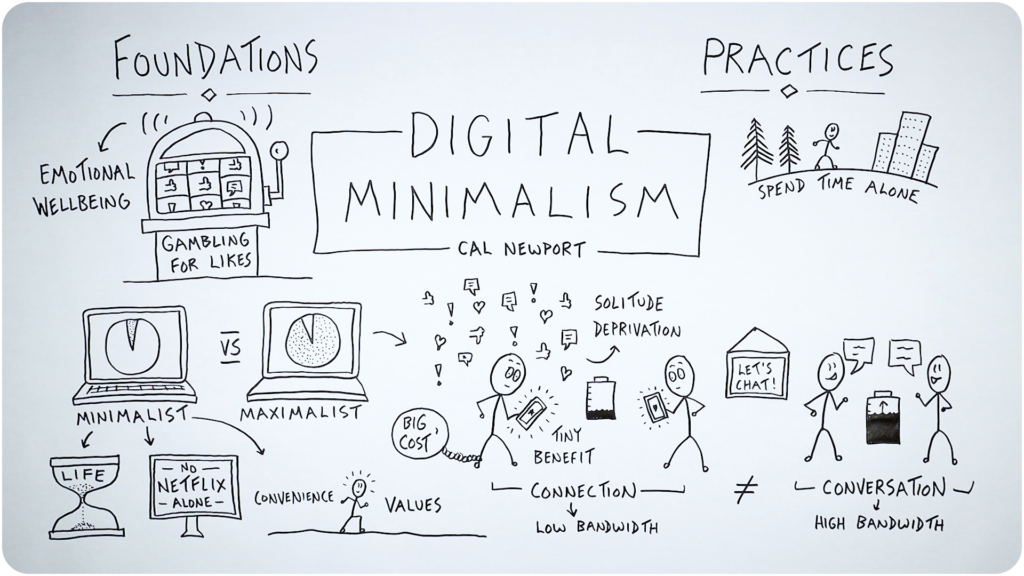

But the type of connection that you get back to is actually pretty important. In fact, Newport makes a distinction between connection (the ability to see what someone else has posted and react to those posts) and conversation (real-time, face-to-face, hearing someone else’s voice).

The connection that occurs through social media doesn’t do much to maintain a relationship because of how low-bandwidth it is compared to real conversations where you’re drawing from facial expressions and tone of voice – that’s high-bandwidth communication that actually does count toward maintaining a relationship.

In that way, social media is kind of the worst of both worlds: you create a state of solitude deprivation while at the same time connecting with others in a way that doesn’t support deep relationships.

One practice that Newport encourages is to hold conversation office hours. Identify a recurring space in your schedule to chat with other people. If you’ve got a long commute home, let your friends know that’s a good time to give you a call, or initiate those calls yourself. Or maybe spend an evening or a weekend morning always at a particular coffee shop, and reach out to friends encouraging them to join you there.

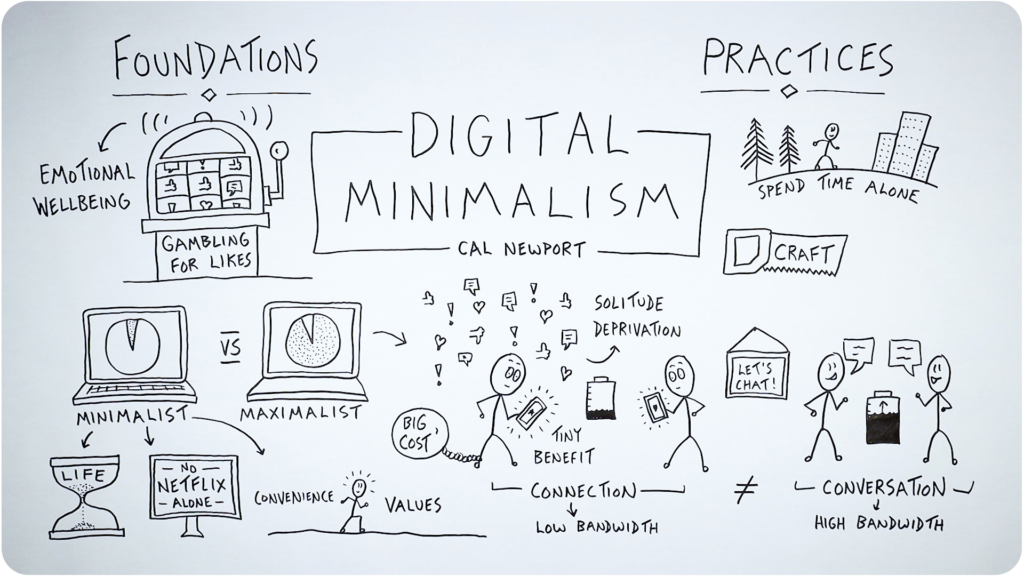

The last push that Newport makes is an encouragement to seek out high-quality leisure, perhaps by identifying a specific craft that you’d like to get good at, even (and especially) when that’s a demanding activity.

In fact, there’s the encouragement here to prioritize those demanding activities over passive consumption, because the energy you expend on high-quality leisure can help to fill your tank rather than deplete it. So whether that’s taking up woodworking or becoming handy around the house or taking up weaving, find a craft that allows you to make something in the physical world.

Another category of high-quality leisure is what Newport calls supercharged socializing. This could be something like gathering friends together for a card game or board game, or even joining a recreational sports league.

The key to supercharged socializing is to seek out activities that require real-world, structured, social interactions. It’s the structure of a board game or a particular sport that takes pressure off of how you’ll socialize, and makes it easier to enjoy the time you spend with other people.

With that as an overview of some of the key ideas, let me next share with you how I’ve been applying them to my life.

Becoming a Digital Minimalist

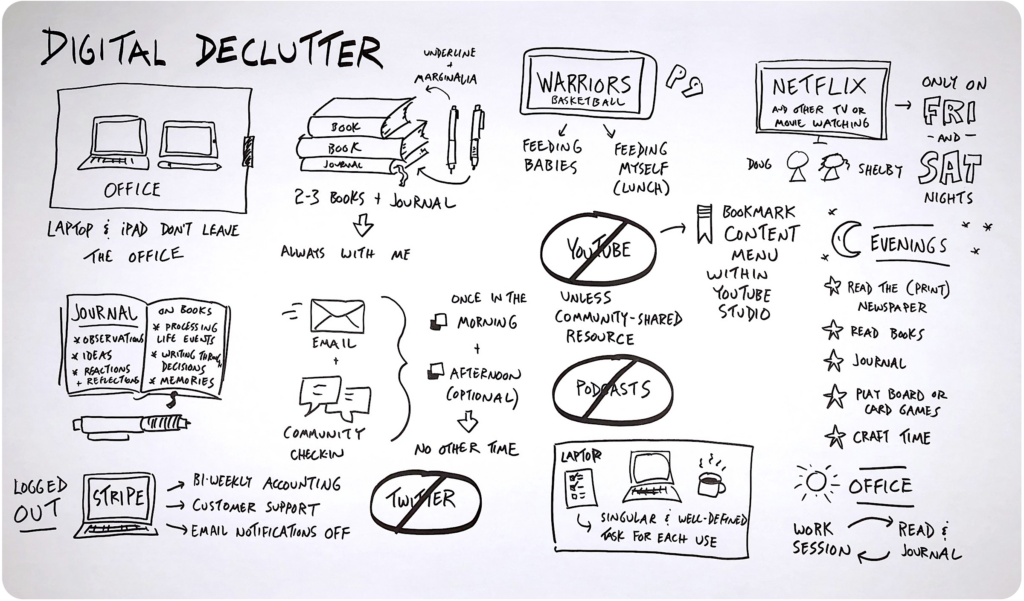

Here’s a quick sketch that I made for myself when I was deciding what I wanted my digital declutter to look like, with the idea of the declutter not being a thing you only do for 30 days, but rather an experiment that you take on to decide what you want to carry with you after those 30 days:

I’ll point out two of the most impactful pieces of my plan.

One was taking on that example that I already shared of not watching Netflix alone. Specifically, my wife and I have identified just two evenings each week that we’ll watch Netflix (or some other streaming service). That’s what Friday and Saturday nights are for, unless we’re doing some other social activity (which, with a couple of babies in the house, doesn’t happen all that often these days).

Instead of defaulting to watching Netflix after dinner every night, we now have a game night set aside on Tuesdays and then the other nights of the week we spend reading, which is related to the other most impactful part of my plan: removing YouTube, podcast, and Twitter consumption from my life.

Even though I’ve been off of social media for a while, I still have the tendency to check a couple of Twitter accounts regularly, watch YouTube more often than I’d like, and listen to podcasts to fill in every gap in my day.

While those aren’t inherently bad sources of media, I’ve found that I enjoy the process of reading books so much more, especially physical books that I can mark up while reading, like I did with Digital Minimalism that supported the creation of the visual summary that I’ve been sharing here.

Rather than filling any little bit of down time by watching a YouTube video or listening to a bit of a podcast, I keep a few books close by that I can pick up and continue reading. What I’ve been surprised at is how good I feel after spending even just 20 minutes reading a book.

That stands in stark contrast to how I often feel after browsing Twitter or watching YouTube. Those activities often either raise my anxiety level, or bring up unhealthy comparisons, or remind me of a bunch of things that I feel like I should be doing that I’m not.

The experience of reading a physical book and the pace of that media consumption hits a sweet spot for me. I’m now long past the 30 days of dedicated digital declutter and I have no desire to look back.

Within the book you’ll find lots of other examples of digital declutters, as well as some practices that I didn’t have time to mention here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed the visual summary that I’ve shared and that it was helpful to hear about how these ideas are impacting my life.

If you’d like to develop the skill of visual note-taking for yourself (perhaps as a high-quality leisure activity), that’s precisely what I teach inside of Verbal to Visual.

I wish you luck incorporating a bit of digital minimalism into your life, and I look forward to sharing more ideas with you next time.

Till then,

-Doug