In business, in politics, in life, it’s far too easy to have a short-term mindset, one where you’re focused on winning the day without considering the long-term consequences of your actions. In The Infinite Game, Simon Sinek encourages us to play a different game.

In this post (a companion to the video above), I’d like to do three things: sketch out some of my favorite ideas from the book, share how I’m applying them to my own business here at Verbal to Visual, and then relate these ideas to the world of visual thinking, for folks who, like me, find it useful to sketch out the ideas they’re working with instead of just thinking about them, talking about them, or writing them down.

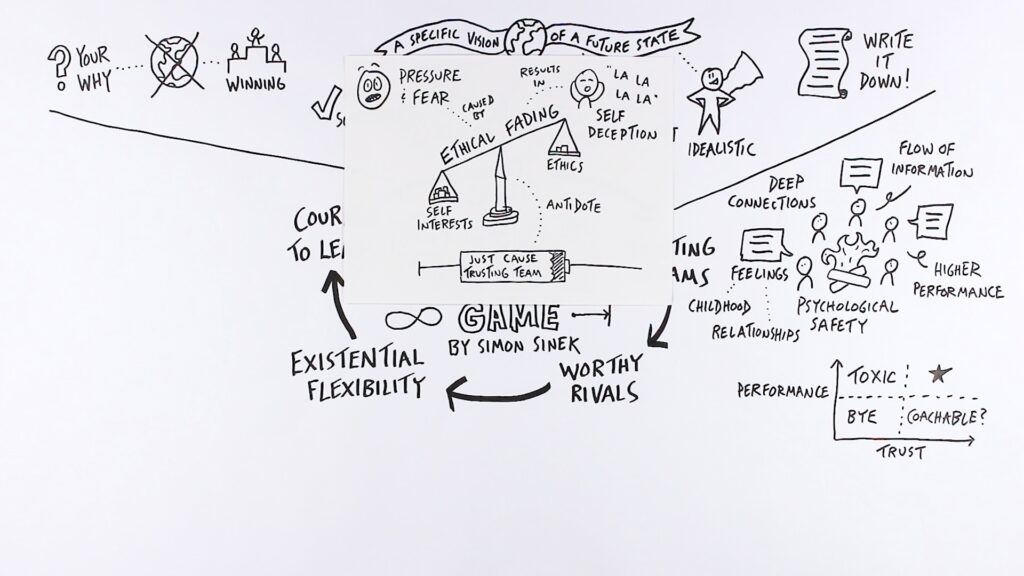

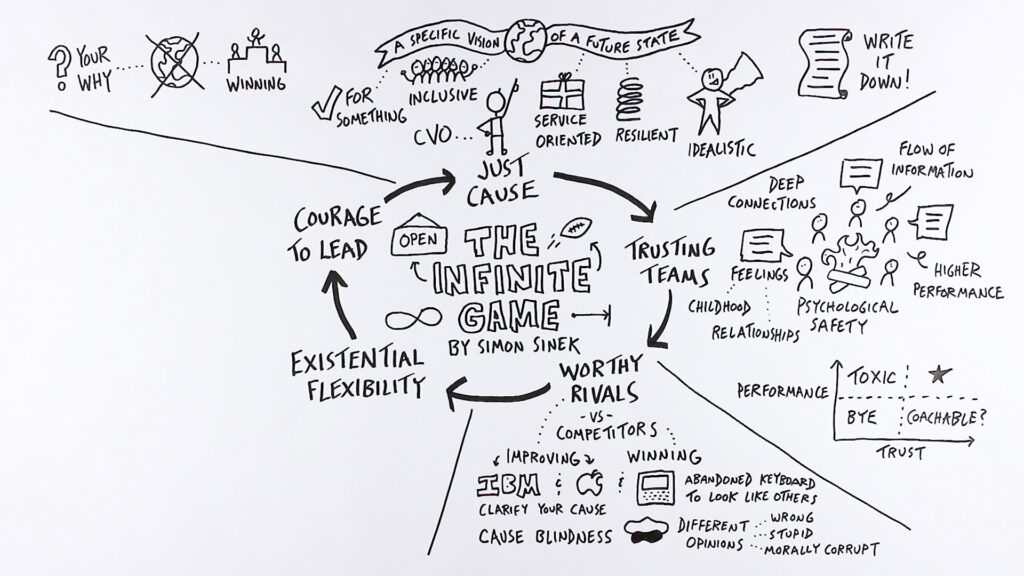

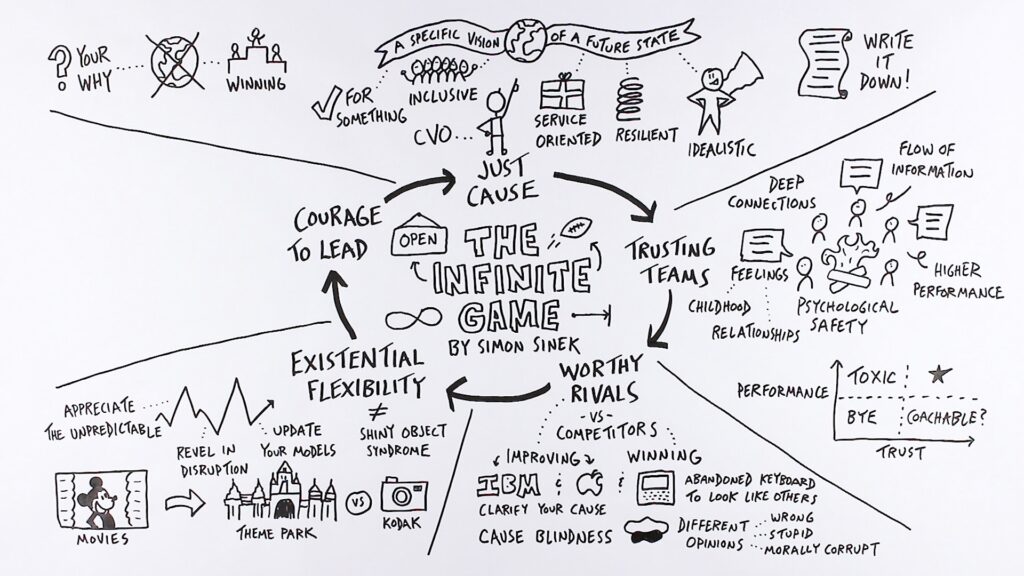

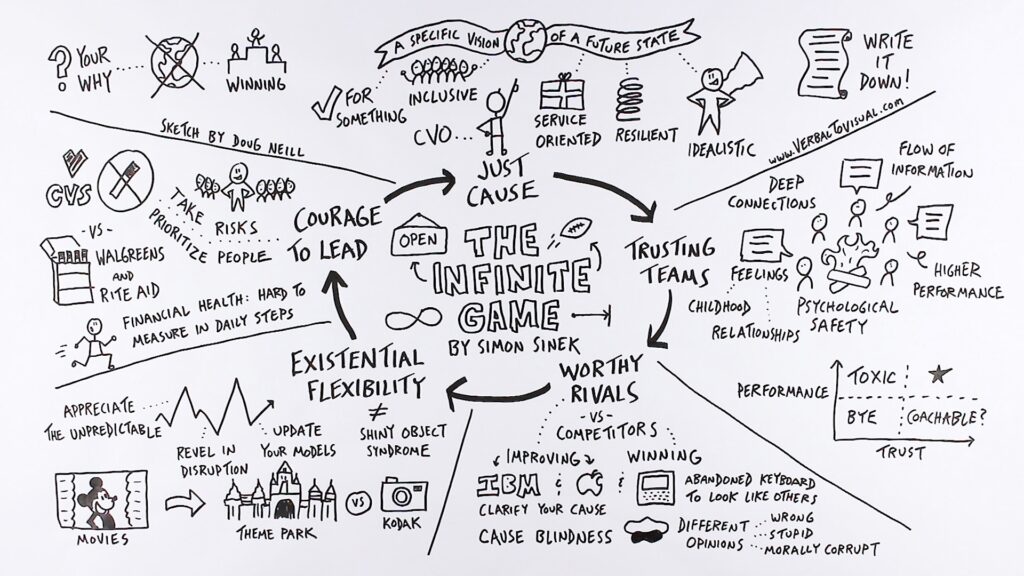

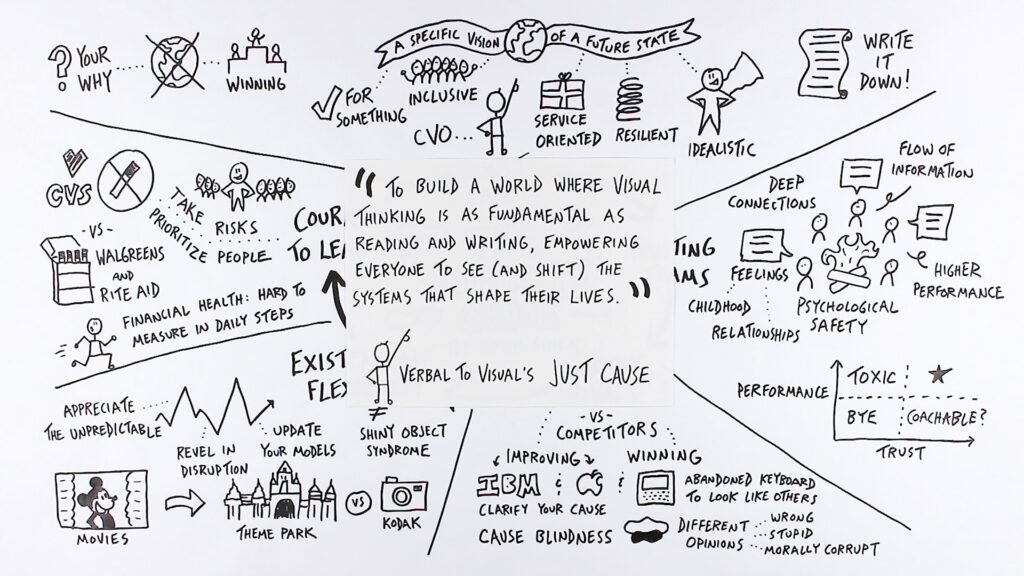

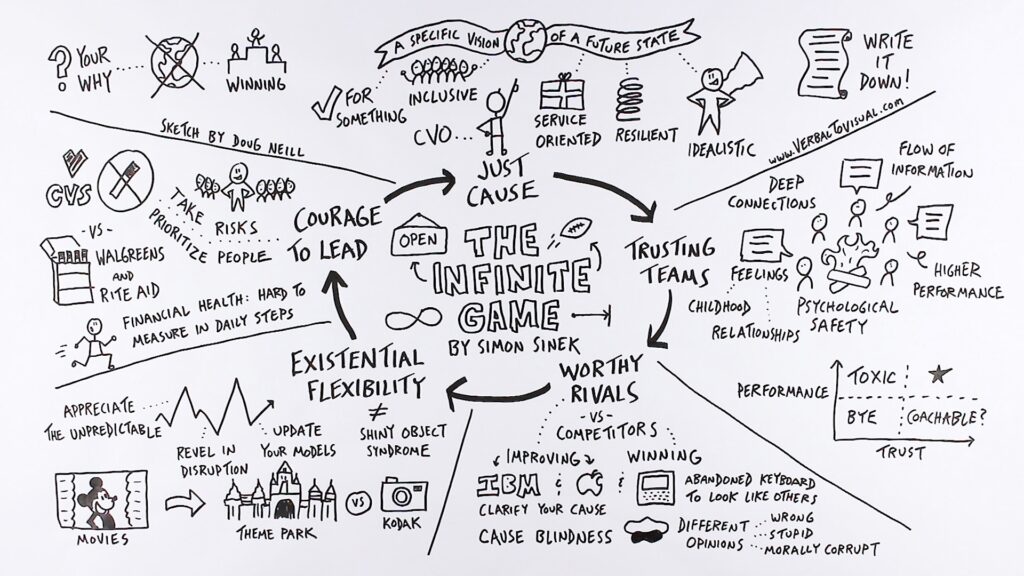

Part 1: The Visual Summary

Finite Games vs. Infinite Games

Sinek begins the book by distinguishing between finite games and infinite games. For finite games, think about football. These games include known players, fixed rules, and an agreed-upon objective that, when reached, ends the game.

As an example of an infinite game, think about business or life. These games include known and unknown players. There are no exact or agreed-upon rules, players play how they want and can change how they play at any time. And there’s an infinite time horizon. The objective is simply to keep playing.

Sinek first came across this distinction in a book by James Carse called Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility.

The main thesis of The Infinite Game is that problems arise when leaders approach an infinite game with a finite mindset. In business, the focus becomes “What can we do to have a great quarter right now? How do we make that line go up?”, regardless of how you’re treating your employees or your customers. When you play an infinite game with a finite mindset, it’s easy to break things that become hard to repair. And those finite practices ultimately make it harder to stay in business or to live a fruitful life.

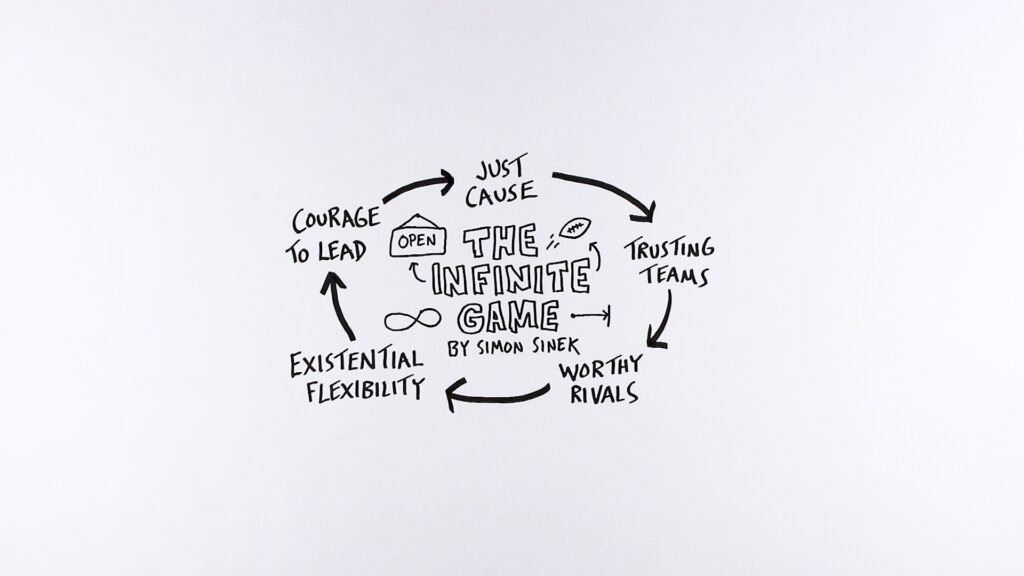

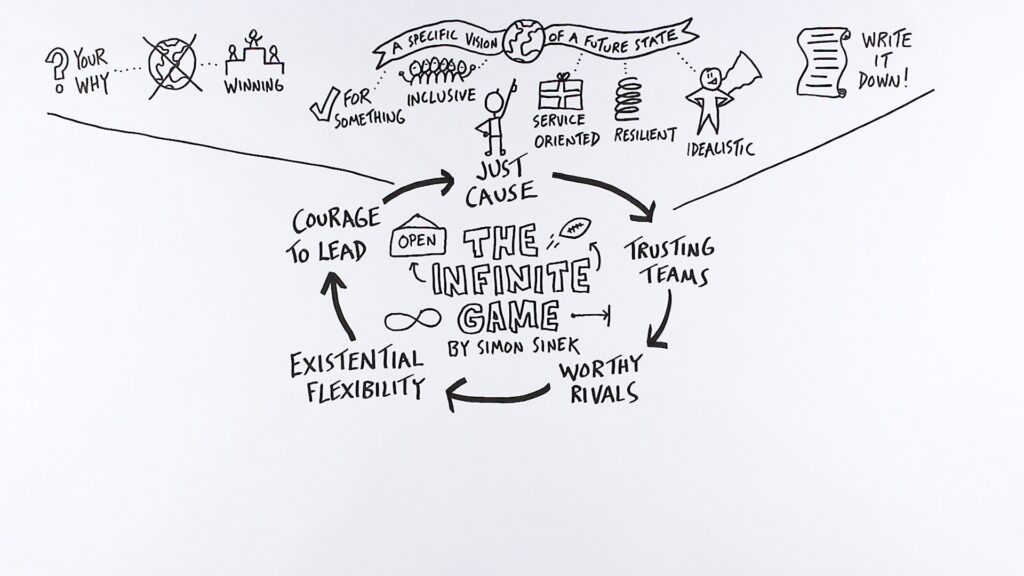

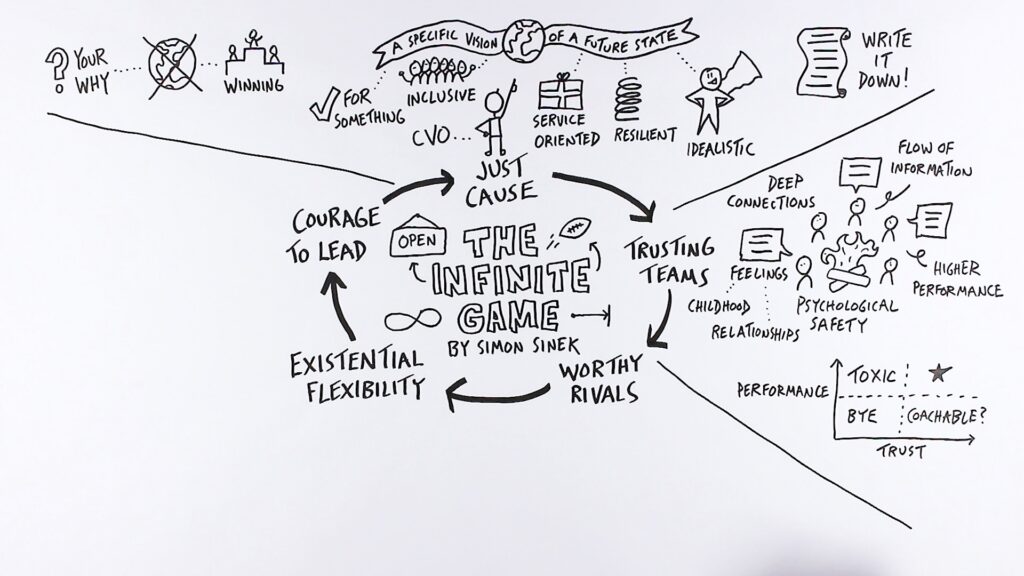

So what does it mean to approach your work or your life with an infinite mindset? Sinek outlines five components: advancing a just cause, building trusting teams, studying your worthy rivals, preparing for existential flexibility, and demonstrating the courage to lead.

Advancing a Just Cause

A just cause is a specific vision of a future state that does not yet exist, a future state so appealing that people are willing to make sacrifices in order to help advance toward that vision. A just cause must be for something, not just against something, affirmative and optimistic. It must be inclusive: open to all of those who would like to contribute, from employees to customers. It must be service-oriented: designed for the primary benefit of others rather than the benefit of the organization. Like a spring, it must be resilient: able to endure political, technological, and cultural change. And like your favorite superhero, it must be idealistic: big, bold, and ultimately unachievable.

Your just cause can’t just live in your head. You’ve got to write it down. The Declaration of Independence is an example of a just cause. And here is Sinek’s: “To build a world in which the vast majority of people wake up inspired, feel safe at work, and return home fulfilled at the end of the day.”

It’s also worth understanding what a just cause isn’t. It’s not the same as your “why.” Your why is about the past, an origin story, the foundation of your organization, while a just cause is about the future you’re working toward. A just cause is not winning, because you can only win finite games, not infinite ones. Winning is about the temporary thrill of a victory, and that’s not going to sustain you on your lifelong journey.

A just cause is not a moonshot. Big, hairy, audacious goals have their place, but a moonshot is finite. If you set one for yourself, make sure you identify the infinite and lasting vision that moonshot will help advance. In that way, your just cause provides the context for all of your other goals.

It’s also not “being the best” (which is just another form of trying to win), it’s not growth (which is a result, not a cause), and it’s not corporate social responsibility (giving money to charity doesn’t alleviate all of the damage you’re causing by playing a finite game).

Building Trusting Teams

In order to advance a just cause, you’re going to need trusting teams. And in order to get a group of people to work well together, a key component that must be in place is psychological safety. Members of that team need to feel safe enough to speak up when they see something that needs to be addressed. When psychological safety exists, there is a better flow of information across the company. People admit their mistakes, ask for help when they need it, and communicate their concerns. When people feel safe at work, they perform better.

So how do you establish that psychological safety? You create the conditions where team members are able to make deep connections with each other. And they do that, as fluffy as it might sound, by talking about their feelings, sharing stories from their childhood, and discussing their relationships. Those types of discussions lead to deep connections and create the psychological safety that results in better information flow and higher performance.

In the building of a trusting team, there’s one thing in particular you need to be on the lookout for. As you consider any individual team member, pay attention both to their level of performance and to the amount of trust they’ve earned amongst the team. A high performer who is also trustworthy is an ideal team member. Someone with low performance and low trust should probably be let go.

But the person to really watch out for is the high performer who isn’t trusted by other team members. That is a toxic individual, often someone more interested in their own career trajectory than the overall team’s performance, someone who hoards information, steals credit, or manipulates younger team members, yet who stays on the team because of their high numbers. In the playing of an infinite game, these team members aren’t worth keeping around. Meanwhile, someone who has lower performance but is trustworthy might be. The question to consider is: Are they coachable?

When you build a trusting team, you’re building for the long haul. Not for short-term wins, but for long-term performance that helps bring about the specific vision identified in your just cause, regularly promoted by the CVO, the Chief Vision Officer.

One thing the CVO needs to watch for is ethical fading. This is a condition in a culture that allows people to act in unethical ways in order to advance their own interests, often at the expense of others, while falsely believing that they have not compromised their own moral principles. Ethical fading is caused by pressure and fear: pressure to hit certain numbers within a certain timeline, and fear that failure means reprimand or termination. It results in self-deception, where you engage in actions you know to be unethical but then make up excuses to feel better about yourself. You come up with euphemisms like “enhanced interrogation” when you’re talking about torture, or “externalities” when that really means harm caused by your production process, or you remove yourself from the chain of causation by saying “it’s not me, it’s the system.”

The good news is that there is an antidote to ethical fading: the combination of a just cause to work toward and a trusting team to work with. With those two elements in place, you feel safe enough to pay more attention to the interests of the team instead of just your own, and you give any ethical considerations that come up their proper due.

Studying Your Worthy Rivals

Building a trusting team helps you be intentional about what’s going on inside your organization. What about what’s going on outside of it? This is where the studying of worthy rivals comes in.

Sinek distinguishes between worthy rivals and competitors. When you study a worthy rival, your focus is on improving. When you compare yourself to a competitor, the focus shifts to winning.

Consider the relationship between Apple, IBM, and BlackBerry. Apple viewed IBM as a worthy rival, considering them the “safe choice” as a foil to help tell the story of what Apple stood for, while still acknowledging the things IBM did well. In that way, worthy rivals help you clarify your why and your cause, and how those are distinct from your rivals.

BlackBerry, on the other hand, viewed Apple as a competitor. With the advent of the iPhone, they abandoned their most distinguishing feature, their QWERTY keyboard, so they could look like the other guys. As Sinek notes, leaders playing with a finite mindset often miss the opportunity to use a disruption event to clarify their cause. BlackBerry could have used that situation to lean into their more tactile approach and their appeal to the professional crowd. Instead, they tried to win the product game.

As you study your worthy rivals, you need to be on the lookout for cause blindness, where you label anyone with a different opinion as wrong, stupid, or morally corrupt. If you default to that approach, you miss out on the benefits of more considered attention to your worthy rival. As Sinek puts it, “Without a worthy rival, we risk losing our humility and our agility.”

Preparing for Existential Flexibility

Existential flexibility is defined as the capacity to initiate an extreme disruption to a business model or strategic course in order to more effectively advance a just cause. This type of flex requires an appreciation of the unpredictable (which is a given in life), an infinite-minded leader who can revel in disruption rather than fear it, and leaders who are willing to update their models when new information comes in.

As an example, consider Walt Disney’s existential flex in 1952, when he stepped away from making movies to find a new way to advance his just cause, which he described as using his art and imagination to offer others a chance to escape their present circumstances and experience the kind of joy he remembered from his childhood, time spent drawing on the farm and exploring the outdoors. This led him to the creation of a theme park, one that could keep evolving forever. As he said, “I’ve always wanted to work on something alive, something that keeps growing. We’ve got that in Disneyland.” That’s a major flex — a completely different business model that advances his just cause as much, if not more, than the movies he helped create.

As a counterexample, consider Kodak during the shift to digital cameras. Instead of seeing new technology as a way to advance a just cause (which could have been framed as “sharing memories with loved ones”), Kodak did everything they could to hold tight to their business model built exclusively around film photography.

It’s important to note that existential flexibility is not the same as shiny object syndrome. It’s not about following the latest trend. It’s about keeping an eye on things, learning from what you see, and updating your models when needed — your mental models about how the world works, and your business models — so that you can meaningfully advance your just cause within that world.

Demonstrating the Courage to Lead

The last component is demonstrating the courage to lead, which involves a willingness to take risks for the good of an unknown future. Consider the decision made by CVS to stop selling cigarettes in their stores in order to stay aligned with their just cause: to help people on their path to better health. They may have lost some revenue because of that decision, but they likely gained other sources, like through the sale of nicotine patches and the newfound inclusion of natural food brands on their shelves, brands that previously wouldn’t stock there because of the sale of cigarettes. Compare that to Walgreens and Rite Aid, who continued stocking cigarettes despite stating a similar cause, a decision Sinek describes as the opposite of courage and conviction, especially considering that 70% of smokers report a desire to quit.

This type of decision highlights the fact that financial health in the infinite game is like exercise: impossible to measure in daily steps. But if you choose to prioritize people over numbers, you’ll likely stay on the right track, acknowledging that in many cases it will take courage to do so.

Part 2: Verbal to Visual’s Infinite Game

It’s one thing to read a book like this and understand the concepts of a just cause, trusting teams, worthy rivals, existential flexibility, and the courage to lead. It’s another thing to actually apply these ideas to your own life or business. So let me explore how these ideas relate to the work I do within Verbal to Visual.

My Just Cause

Here’s what I’ve come up with for Verbal to Visual’s just cause: To build a world where visual thinking is as fundamental as reading and writing, empowering everyone to see (and shift) the systems that shape their lives.

If you’re new to the term “visual thinking,” at its core it involves getting ideas out of your head and onto the page in the form of a drawing or diagram, not for the purpose of creating art, but for the purpose of seeing those ideas with more clarity by tapping into the visual processing powers of your brain.

You can go a lot of different directions with visual thinking. I’m finding it helpful to look at the intersection of visual thinking and systems thinking, because so much of our lives are dictated by external systems and internal systems. It’s not until we can see those systems and point to their different parts that we can begin to shift them where needed to improve our lives and the lives of others.

Does this just cause check the five boxes? It is indeed for something — it’s for visual thinking. It’s inclusive because anyone can join along, whether or not you consider yourself a visual thinker (because if you’ve got eyes, then you already are). It’s service-oriented because it’s focused on empowering you with a particular skill set for a specific purpose. It’s resilient to technological change because you can use pen and paper, tablet and stylus, or VR headset and hand gestures to engage in visual thinking. I think it’s also resilient to cultural and political shifts, because there will always be a need to understand, map, and communicate the various systems that shape our lives. And it’s idealistic because of the phrase “as fundamental as reading and writing.” That’s a big, lofty goal to work toward, where the skill of visual thinking lives right alongside the skill of reading and the skill of writing. In all likelihood, we’re never going to get there. But even if we’re just able to bring those ways of thinking closer to each other, if the act of sketching things out becomes a more common way of processing the complex things we’re working with, that’s a win.

My Trusting Team

At the moment, Verbal to Visual is a company of one. It’s just me, no full-time employees or independent contractors. But I do have a trusting team: I consider the Verbal to Visual Community to be that team. Within Verbal to Visual, there are self-paced online courses that folks can work through on their own time, but I also host weekly live workshops where I get to have conversations with people who are developing their visual thinking skills and, in one form or another, advancing a just cause similar to my own.

As much as those live events are about skill-building and troubleshooting, there’s also a huge component of psychological safety. The members of that community feel comfortable sharing the things they’re working on and their feelings about it. They’re able to make deep connections with other visual thinkers, be inspired by the work of others, and share information with each other, ultimately reaching a higher level of performance, no matter what area of life they’re directing their visual thinking skills toward. This can be a personal skill you use for your own learning, or it can be a public and professional skill that you bring into your workplace as you take on the role of sense-maker and meaning-maker through the creation of helpful visuals.

My Worthy Rivals

There are plenty of others who are teaching visual thinking skills. I tend to think of them more as colleagues rather than rivals, because it is a very supportive community. But I still appreciate Sinek’s distinction, and how the studying of rivals can help you improve your craft and clarify your cause. I enjoy learning from people like Emily Mills, Dan Roam, Mike Rohde, Kelvy Bird, Brandy Agerbeck, and Dario Paniagua, among many others.

I learn from these “rivals” in a few different ways. First, I can learn new visual thinking skills and approaches. I can improve my craft by studying and learning from these individuals. That’s even built into the way I run the Verbal to Visual Community with our annual book club. Each quarter we read a couple of books together, alternating between good nonfiction books (like The Infinite Game) and visual-thinking-specific books. With a book like The Infinite Game, the goal is to create some sort of visual summary. With a book like Generative Scribing, the goal is to learn and apply the visual thinking techniques shared in that book.

The second way I can learn from my rivals is by paying attention to how they teach — the structure of their books, their online programs, their marketing strategy, their business model. That’s the area I spend less time on because it makes it too easy to fall into shiny object syndrome. But it is something I pay attention to, and it can inform shifts I might make in my own models.

My Existential Flexibility

Keeping in mind my just cause, what would it look like to initiate an extreme disruption to my business model or strategic course in order to more effectively advance it?

To build a world where visual thinking is as fundamental as reading and writing, empowering everyone to see (and shift) the systems that shape their lives.

Let me first acknowledge that this just cause is newly defined. I’ve had mission statements and website taglines, but it wasn’t until the creation of this post that I was forced to frame what I’m up to in this particular way. And so far, I’m finding it to be very powerful, both the aspect of bringing visual thinking on par with reading and writing, and the emphasis on seeing and shifting the systems that shape our lives.

The core of my business model over the last decade has been my own online learning program, that blend of courses and community that I mentioned earlier. It’s an effective way of advancing my just cause, one individual at a time. But it’s limited to the type of individual who is interested in signing up for an online course or community and has the means to do so.

I think there might be two other places where I can advance this just cause, which would involve an update to my business model (one that I’ve experimented with in the past). Those two areas are the world of education and the world of business. I’ve already built a resource for educators called Sketchnoting in the Classroom, and I think there are things I can do to strengthen that program and better support educators who want to develop these skills and share them with their students. And then there’s the potential to bring these skills into organizations in the form of custom workshops for a specific group of people, helping that group build and apply these skills within the context of their work, and helping that organization advance their own just cause.

On the marketing side, my focus is on YouTube, specifically the creation of visual book summaries. Something new I’m trying with the video above is doing three specific things: first, I share a condensed visual summary of the book; then I talk about how I’m applying those ideas to my own life and work (with the hope that you’re doing the same); and then I speak directly to visual thinkers, advancing my just cause within the scope of the particular book. It does make for a longer video and post, and it may or may not work. But it’s a format I’m excited to try. I’m also reminding myself to stay flexible in case it doesn’t end up advancing my just cause and I need to find a new format that does.

My Courage to Lead

In what way might I demonstrate the courage to lead? How might I take risks for the good of an unknown future, prioritizing people over numbers along the way?

There’s a tangential connection here to the example of CVS removing cigarettes from their shelves, specifically the comparisons that have been made between smoking and social media, and the negative health consequences associated with each. Physical health consequences in the case of smoking, mental health consequences in the case of social media (though the line between physical and mental health is plenty blurry).

How this relates to a risk I’m taking right now is through an emphasis on slow media. “Slow” is my word for 2026. It relates to Slow Productivity by Cal Newport and Sustainable Ambition by Kathy Oneto, which are the two books we’re reading for the first-quarter 2026 Verbal to Visual Book Club.

For me, slow media involves spending less time on YouTube and more time reading books and articles (some of which I might sketch out in a video). As much as I appreciate the platform, spending too much time on it doesn’t improve my life.

Alongside that slow media consumption, I’m also experimenting with slow media creation. Instead of trying to churn out as many videos as I can as quickly as possible, I’m taking more time with them. I’m focusing on one good book at a time, doing my best to sketch out the ideas that make it interesting, and then taking the time to relate those ideas to my own life and work, and then to the world of visual thinking.

In the case of slow media consumption, I’m prioritizing myself. In the case of slow media creation, I’m hoping to prioritize you. It might seem like I’m not prioritizing your time with a longer video, but my hope is that there’s a place for this type of longer discussion that moves away from the short-term dopamine boost that comes with the infinite scroll.

Part 3: The Infinite Game of Visual Thinking

This is the part where I speak directly to the visual thinkers, the sketchnoters, the graphic recorders, and anyone who saw my just cause and immediately said “heck yeah, I’m in.”

Here’s my message to you: Visual thinking isn’t a skill that you master and then check off. It’s an infinite game that you commit to playing. There’s no moment when you “win” at visual thinking or reach the final level. Instead, the goal is to keep practicing, keep improving, and stay open to new applications of this skill.

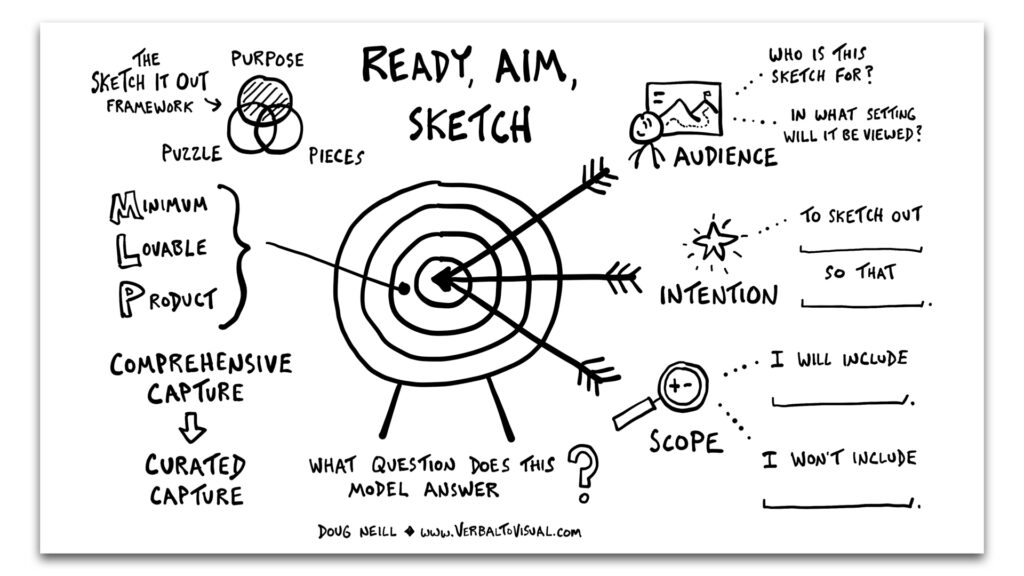

Your Just Cause

In order to approach visual thinking as an infinite game, it will help you to have a just cause. On the micro level, that can exist within an individual sketch. If you’re familiar with the Verbal to Visual Curriculum, this is where the lesson “Ready, Aim, Sketch” comes in, where you identify the audience, the intention, and the scope of a particular model you’re sketching out.

But I think it might also be helpful to craft a bigger-picture just cause behind your visual thinking work. What specific future state are you helping to bring about? It doesn’t have to be global in scale, like Sinek’s and mine is. That vision could focus on your own future state, or the future state of your family, your community, or your organization. Instead of “to build a world in which,” it could be “to build a family in which,” or “to build a city in which,” or “to build an organization in which.”

What I’ve found is that when you frame your efforts around a just cause, it takes away some of the personal pressure you might feel to perform at a particular level or to create visual work that has a perceived aesthetic quality to it. You instead focus on the just cause that you’re advancing. It becomes less about you and more about the future that you’re working toward.

Your cause likely isn’t directly related to visual thinking. But you can use your visual thinking skills to advance it, like in the first part of this video where I’m using the skill of visual thinking to help advance Simon Sinek’s just cause, to help bring about a future state where more leaders embrace the infinite game and play with an infinite mindset instead of a finite one. You can use your visual thinking skills to make the systems related to your just cause more visible, so that you can then shift them in the direction they need to go.

Your Trusting Team

As a visual thinker, there are two teams you might consider. One is a learning community, where you surround yourself with other visual thinkers. That learning community could be Verbal to Visual if my work resonates with you, or it could be within another branch of the growing community of online visual thinkers.

The second team you might consider gathering is one that focuses on your just cause. Who else within your local or online community is working to advance that same just cause? And how might you gather together to support each other?

There’s also a third team I’d like to talk about more in the future, and that’s your internal team. This relates specifically to the book No Bad Parts by Richard Schwartz, which lays out the Internal Family Systems model. (There’s that word “systems” again.) In this case, it’s the system of different voices and feelings that come out in different ways, in different contexts, and that have a big impact on how you perceive and act in the world. If you want to spend some time exploring that internal team, join us for the upcoming book club where we’ll be reading and sketching out that book together.

Your Worthy Rivals

I encourage you not to worry about being as good as, or better than, any other visual thinker whose work you admire. Instead, learn from them. Study their work. Identify what you enjoy about it, and what techniques or approaches you might weave into your own work.

Don’t make it about comparison or competition. Instead, make it about improving.

Your Existential Flexibility

Existential flexibility for visual thinkers shows up in a couple of ways. The first is the willingness to update your models. Even though you sketch things out in one particular way that works in the moment, acknowledge that future information might lead you to update that model. The visuals you create aren’t set in stone. It’s not about framing them and putting them up on a pedestal. Instead, it’s about the willingness to sketch them out again, to adjust them when needed to better fit the reality of the situation. Like a good scientist, I encourage you to get excited when new information throws a wrench into your theory, when it makes your model not quite work as well as it used to.

I think you also need to have the flexibility to adapt your tools and techniques to the needs of the project in front of you, responding in real time as necessary. The great (and sometimes challenging) thing about visual thinking is the fact that there are so many different modalities you can work in. You can work large-scale with poster paper and markers, small-scale with sticky notes or index cards, analog in physical notebooks, or digitally with a tablet and stylus, choosing from hundreds of apps. Instead of letting that overwhelm you, I encourage you to use the tools that are most accessible, and be willing to change up your tools and techniques once a given approach stops working for you, once you’re no longer advancing your thinking but just running in circles.

Your Courage to Lead

What does it mean to demonstrate the courage to lead as a visual thinker? I think it means being willing to put your models out there, to share them with others. Not necessarily with everyone on the internet (though there are plenty of benefits to doing that), but maybe just with a friend who would benefit from hearing about the book you just read, or your family when you want to change up the dynamics of your days and weeks, or your team at work when you recognize a dysfunction that needs to be addressed.

I get that it might feel risky to share visual work in that way. But trust me, it will be worth it. And you won’t get nearly as much critique around the quality of your visuals as you might think. In that way, you are prioritizing people, because I believe there are people who will benefit from your visual thinking work, from the sense-making and meaning-making you do when you take the time to create a visual artifact. You’d be doing them a disservice if you don’t share it with them.

I think you can also look for opportunities to prioritize your own life by building a sustainable visual thinking practice that chooses depth over speed and iteration over perfection. Similar to our discussion of financial health, the impact of your visual thinking work might be hard to measure on a daily basis. But if you show up consistently and share consistently, whether online or in person, you’ll start to attract the people who resonate with your work, people who will help you advance your own just cause.

I hope you’ve found this sketch and this discussion to be useful. For more on how to build your own visual thinking skills, check out the full Verbal to Visual Curriculum or sign up for the newsletter to stay in touch. For more on The Infinite Game, go pick up the book yourself and follow along with Sinek’s work on YouTube as well. I look forward to sharing more good ideas and good books with you soon, with the goal of continuing to advance my just cause. I wish you luck with the advancement of your own.